Welcome to the BEAM Blog!

BEAM Summer Away Faculty Reflections

BEAM is currently hiring summer faculty for Summer 2022. If you are interested in working at one of our programs, please apply here.

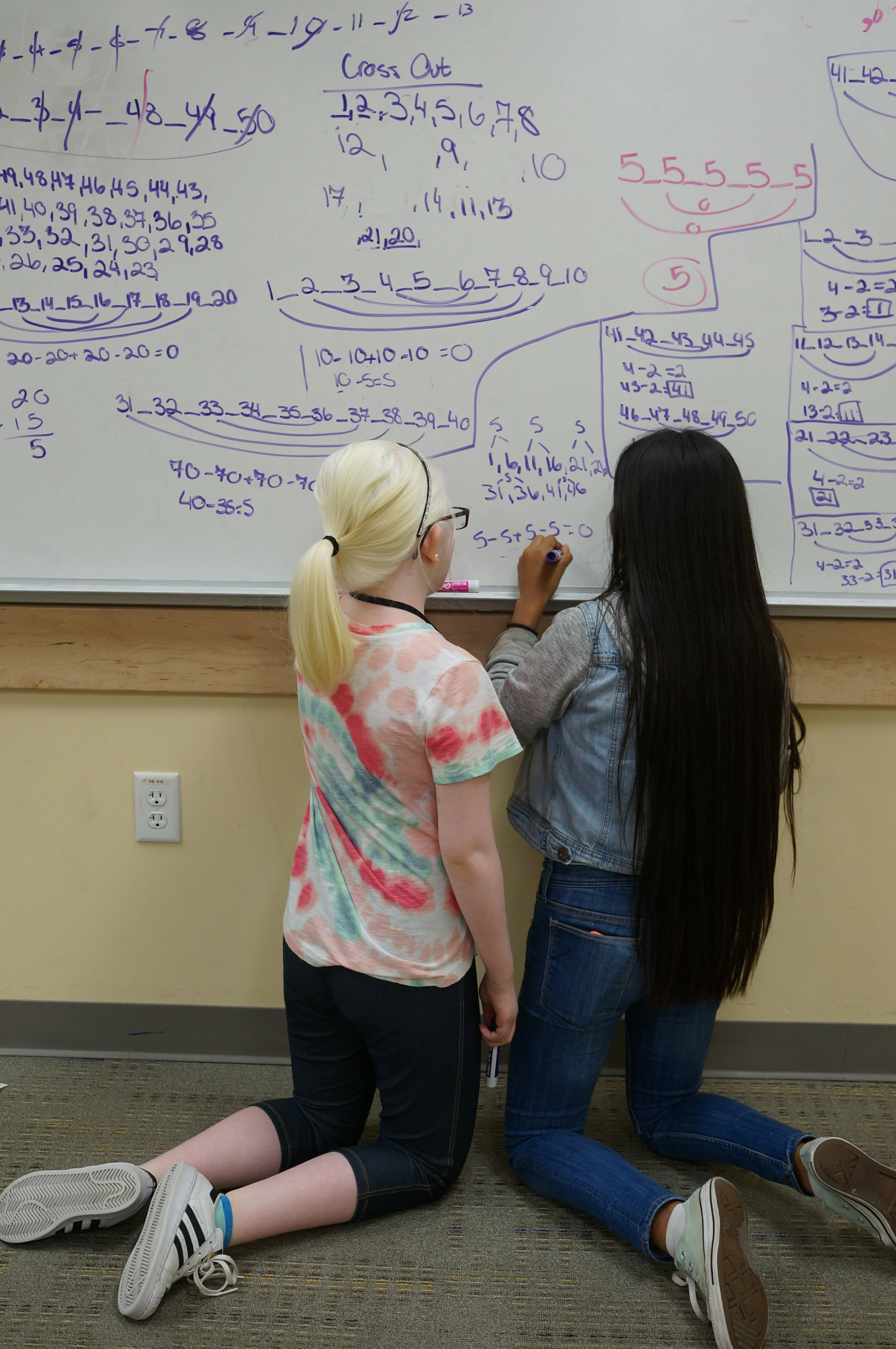

BEAM’s summer staff members are what make our summer programs special. Knowing how much we get from our staff, we recently asked some of our long-time Summer Away faculty what they’ve gotten from working with us. The answers we got were resoundingly encouraging.

What we consistently heard was that our faculty learn from our students just as our students learn from them. Our staff learn how to be flexible, how to connect with students in a way that makes them more excited about math, and how to bring the spirit of mathematical exploration and discovery back to their year-round jobs. Here’s what our faculty have to say:

Tanya Finkelstein

For Tanya, one of the most special things about BEAM students is how much they can figure out on their own. With only a definition, they can really run! Of course, letting students run requires curricular flexibility and a willingness to be confused that most teachers are taught not to have. It’s a learning experience:

“The most important way you’ll grow as a BSA faculty is learning not to have expectations, which so many teachers come in with. Teachers are taught to have expectations of themselves that they’ll always have the answers and know how to guide their students to the solution. The most important thing kids need from you is to guide them along their own path to the answer without an expectation of what that path will look like. Some of the best teachers I’ve had in my life were kids. A teacher should be ready to feel challenged. It’s important to be confused yourself and make sense of things in front of the students so they can see a model of exploration. This is how you grow over time with BEAM.” – Tanya Finkelstein

Siddhi Krishna

Siddhi has taught both Cryptography and Knot Theory every year she’s been with us, but her classes have never looked the same twice. Siddhi attributes this to the fact that the direction the class goes depends on what the students are buzzing about any one summer. Bringing the exploratory culture of BEAM classrooms to her year-round teaching has ultimately translated to better outcomes for her year-round students. In her own words:

“I’ve learned how to listen much more closely to what students are saying. I’ve also learned to ask better questions. When a student says something, you want to draw the best thing out of them without telling them the answers. What BEAM does well is create a culture where students aren’t expected to know the answers. Trying to inject that spirit into my teaching at the university level has been important. Making it clear I don’t expect you to know the answers, but I do expect you to ask questions and try to bridge that gap, has made a difference in what my students get out of my college classes.” – Siddhi Krishna

Andre Mathurin

For Andre, teaching with BEAM was a stark contrast to the formulaic, almost sterile culture of mathematics education that exists in most high schools. Being able to think about big concepts and problems without the overhead of midterms or standardized exams was not only personally motivating for Andre, it also helped him learn to better connect with students in his year-round position.

“My first summer I had this idea that it would be super structured. I realized that you can have a game plan and that’s fine, but the need to be flexible and meet students where they are is important. That’s one of the big learnings I got from BEAM, how to leverage students by getting them to work together and make it about discovering math versus me being the one to point things out to them. One of the incredible things about BEAM students is that they really can do this. They leave the summer program being better thinkers and better communicators.” – Andre Mathurin

Cory Colbert

Cory has worked with BEAM every summer since 2014, and he’s taught topics ranging from Analytic Number Theory to Aviation Theory. Working with BEAM has not only given Cory the same tools for leading a discovery and exploration-based classroom as other staff, it’s given him a vehicle to reflect on how he thinks about equity in STEM more broadly:

“I used to not think very explicitly about equity, diversity and inclusion, especially in 2014. I think I had gotten so used to being the only Black person in a classroom (or one of the only), and one of only 2 Black graduate students in math at my school (out of over 100), that I think I grew numb to how much STEM struggles with diversity… Recently, with regards to teaching, my focus has been on combating bias and micro-aggressions in the classroom. For example, my women students are less likely to volunteer an answer than their male counterparts. So, I'll make extra efforts to encourage women to share their results with the class, which are usually right, by the way... My hope is that maybe BEAM faculty can learn how to be effective anti-racist teachers both at BEAM and elsewhere.” – Cory Colbert

BEAM is currently hiring summer faculty for Summer 2022. If you are interested in working at one of our programs, please apply here.

...And Now for Some Math

In the newsletter, we shared problem 64 from this year’s 100 Problem Challenge. Before we dive into solving the problem, we hope you’ll take some time to work on the answers and uncover a pattern…

In the newsletter, we shared problem 64 from this year’s 100 Problem Challenge:

Remember how squaring works: a number with a 2 exponent should be multiplied by itself. For example, 52 = 5×5 = 25 or 102 = 10×10 = 100.

If

12 + 22 + 32 + 42 + ⋯ + 242 + 252 = 5525 (First Equation)

How can you figure out the following two sums without adding up all the terms?

2 2 + 4 2 + 6 2 + 8 2 + ⋯ + 48 2 + 50 2 = ??? (Second Equation)

3 2 + 6 2 + 9 2 + 12 2 + ⋯ + 72 2 + 75 2 = ??? (Third Equation)

Before we dive into solving these two equations, we hope you’ll take some time to work on the answers and uncover a pattern…

Enough delays, here is the solution!

Let's start off first with the solution, and then with some discussion of why we use this problem at BEAM.

As a BEAM student, I might first want to make sure that I know the meaning of the ellipses in each equation; it means that the pattern repeats in the same way all the way through to the last listed elements. For example, in the first equation, I continue after 42 with 52 + 62 + 72 and so on (This is always the first step of a problem: make sure you understand it!).

These problems are pretty tricky if they're new to you, but once you see it, the solution is fairly straightforward. If I want to solve this problem without adding up all the terms (or computing some of these larger squares!), I should look for a relationship between each statement. The second equation seems to have the sum of square multiples of 2, and the third equation has sums of square multiples of three. Does this mean I can just multiply each equation by 2 and 3 respectively? How can I be sure?

A bit of care shows you that right away. 42 isn't twice as big as 22; it's four times as big (16 vs 4). Similarly, 62 isn't three times as big as 22 , but nine times as big (36 vs 4). If the pattern holds true for each element in the second sum, then each element there will be four times larger; in the third sum, each element would be nine times larger. That pattern does indeed hold true, so the answers are 5525⋅4 = 22,100 and 5525⋅9 = 49,725.

12 + 22 + 32 + 42 yields 1 + 4 + 9 + 16

22 + 42 + 62 + 82 yields 4 + 16 + 36 + 64

32 + 62 + 92 + 122 yields 9 + 36 + 81 + 144

Our hope is that a BEAM student would at this point realize that this isn't just about these two sums; 42 + 82 + 122 + 162 + … + 1002 will be 16 times as large, and so on and so forth. Proving this is not too difficult once you think about it the right way. For example, (2n)2 = (2n)(2n) = (2⋅2)(n⋅n)=4n2 . In general, if you make the number being squared x times bigger, you get (x⋅n)2 = (x⋅n)(x⋅n) = (x⋅x)(n⋅n) = x2n2. Rather than multiplying the result by x, you multiply by x2.

So, why do we like this problem for BEAM students?

There are lots of things that make it compelling. For one thing, the sense of misdirection—where it's not two times larger, but four times larger—makes it compelling. It also helps build skills at both abstraction and generalization. Students learn to work with the ellipses and they're also quickly pressed to generalize from doubling each squared term to other possibilities. For students who haven’t worked with algebra, expressing that is a useful challenge.

Finally, it naturally motivates the relatively simple proof for why the pattern holds; students feel a genuine need for the proof when they see it, because the result was surprising. Motivating proof can be difficult; this problem, with its relatively simple justification, can drive that motivation.

Our 100 Problem Challenge has a mix of problems. You’ve seen more challenging problems in past newsletters, but the mix is important to give entry points to all students and drive growth in new ideas.

BEAM Pathway Student Summer Reflections

Each summer, BEAM helps students in our 9-year Pathway Program find summer enrichment programs to help pursue their interests in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Students have participated in PROMYS, MathPath, and many different pre-college programs. This August, we spoke with three different BEAM students about how they spent their summers.

Each summer, BEAM helps students in our 9-year Pathway Program find summer enrichment programs to help pursue their interests in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Students have participated in PROMYS, MathPath, and many different pre-college programs. This August, we spoke with three different BEAM students about how they spent their summers.

Helen, BEAM Summer Away 2019 Bard College

This summer, Helen chose to take the Project Gateway course at the Summer STEM Program at Cooper Union. Helen wrote to us after she finished the program:

Helen is a tenth-grader in New York City.

“In this course we became civil engineers, investigating how design and engineering impact our communities. Throughout the three weeks of the program, we created a journal where we went outside and looked at the way our neighborhood was engineered and what effect it had. We also learned how to use AutoCAD, a software program for computer design. Personally, using AutoCAD was the project I was most proud of and enjoyed doing since I’m very interested in computer designing. Our final project was to pick a neighborhood in NYC and redesign the neighborhood. My group and I focused on Clinton Hill, Brooklyn. We improved the traffic, repaired the streets, and made the neighborhood more family-oriented. Since we were learning remotely, we had the opportunity to go on a field trip to a compost yard and learned how composting works and how they compost in NYC throughout all the seasons which was very interesting. In the future, I would like to be part of the Summer STEM program at Cooper Union again and explore a different engineering course.”

Helen’s CAD drawing of a one bedroom apartment she visited.

Kenny, BEAM Summer Away 2020 Los Angeles

This summer, Kenny participated in MathPath, a four-week enrichment program for middle school students who show high interest and promise in mathematics. Courses include math history, combinatorics, graph theory, and more. Here’s what Kenny told us about his experience at MathPath:

Kenny is a ninth-grader in Los Angeles.

“For the math part of the program, we had problems that challenged us and made us think really hard about how to solve them. Sometimes it took more than that. We did a lot of probability and thought about how many ways could a certain event take place. My favorite part had to be the moments when classmates helped each other out to solve one problem. We all took turns and disagreed respectfully. I enjoyed working with them since I heard many ideas and had fun while talking. BEAM helped me get ready for MathPath by teaching me the skills that I would need to better understand the math problems.”

Rubi, BEAM Summer Away 2019 Los Angeles

She spent 12 weeks with Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Talented Youth, learning about many different facets of Forensics, from its history to its current application. Rubi wrote to us about the most interesting project she worked on:

Rubi is a tenth-grader in Los Angeles.

“The class for Introduction to Forensics was challenging but it was also fun. I had a great time learning about the wide variety of topics in the class. The most interesting thing we did, in my opinion, was determining blood types. We were given sample blood types with liquids that could be used to change the color of the blood so we could determine what type the blood was. The way BEAM helped me get ready for this class was by giving me access to the materials I needed. They bought the materials, including a microscope, forensics pack, and books, without hesitation.”

Summer 2021 in Review

Building on what we learned last summer, we made key changes to our online tools and other program elements to build a strong community and encourage students to dive deep into problem solving this summer. After the program, Ayaan told us, “This summer made me realize that the math I enjoy is the creative, puzzling kind.” Here are some highlights…

Building on what we learned last summer, we made key changes to our online tools and other program elements to build a strong community and encourage students to dive deep into problem solving this summer. After the program, Ayaan told us, “This summer made me realize that the math I enjoy is the creative, puzzling kind.” Here are some highlights:

Challenge Accepted

Every summer, Discovery students participate in the 100 Problem Challenge, 100 fun and difficult problems that lead students towards the idea of mathematical proof. This year, students solved three times more problems than last summer, and one student solved 20 problems on his own — a new BEAM record! Another student told us he especially enjoyed these problems because they engaged his “big brain energy.”

Everybody loves pasta!

At the beginning and end of each day, students and counselors met with the same small group so they could really get to know each other (which happens naturally when we’re in person, but is harder to recreate online). While doing a morning icebreaker, one group quickly realized that everyone’s favorite food was pasta. From then on, everything they did was pasta themed!

Can we chat?

BEAM students couldn’t get enough of Zulip, our online chat platform, which served as a sort of virtual lunch table, with lots of students sharing inside jokes and memes. Counselors posted daily polls that pulled even shy kids out of their shells. Students could also earn “badges,” in the form of emojis that appeared next to their names on Zulip. Some got a 👻 for solving the Problem of the Week, 🏆 for working on a team, and special emojis for counselor challenges, like ✊ for telling Ngoc your favorite joke! Badges were so popular, we're planning to use them at our in-person programs.

Persevering through tough problems

At OMT, students work on math of their choosing on their own or with others. This year, we expanded OMT to give students more time to work independently on the math they love. Mia chose to work on the Problem of the Week during her first session. After the session was over, she said, “My goal was to give it my all. I didn’t give up and I kept strategizing how to solve it.”

BEAM Students Think Big

A couple of our favorite comments from the summer:

“BEAM has changed my perspective of learning forever. This program has helped boost my confidence, makes me love math and learning, and shows me skills that will help me in the future. I am excited about my classes showing things like new math vocabulary, patterns, and skills that make my brain feel satisfied, and how to prove my theory/conjecture is correct.”

“I like that there are a lot of ways to solve a problem and I like that there’s math in anything and everything. It’s like a universal language that not a lot of people can speak but when you finally get it, it’s just such an incredible feeling of ‘I did that.’”

Announcing BEAM NYC High School Results!

High school admissions were turned upside down in New York City this year.

The pandemic forced major changes in the admissions process and meant families faced delays and uncertainties. Under-resourced middle schools, still struggling with online learning, were often unable to help students.

That’s where BEAM stepped in, to fill the gaps and provide the support students and their families needed to successfully navigate the process.

BEAM 8th graders, with our help, earned admission at great high schools this spring!

Results to date:*

86% of BEAM 8th graders earned spots at high schools BEAM rates at Trusted+. These are schools we think have good course offerings and support.

54% of BEAM 8th graders earned spots at high schools BEAM rates as Tier 1. Tier 1 high schools offer Advanced Placement calculus or its equivalent (like the opportunity to take a college-level math course), and more than 85% of graduates are prepared for college. BEAM counts only about 40 high schools citywide, or about 7% of New York City high schools, as Tier 1; all are highly selective for admissions.

12 BEAM students were admitted to Specialized High Schools, including Stuyvesant, Brooklyn Tech, and Bronx Science.

In New York City, what high school you attend determines a lot about what opportunities you’ll have in the future. So, we know it’s important to find a strong, good-fit high school. Given all the uncertainties right now, finding a strong school was even more vital this year.

BEAM provides individualized support to our students and their families throughout the admissions process. This year, we also built an online high school admissions portal to connect students and their families to even more resources.

Here’s what Brandon C. said about his admissions experience:

“The high school admissions process was smooth for me. BEAM made this possible. They were able to give me a list of top schools that fit my interests. From there I looked through the schools and made a list and then ranked them based on what they offered and what I liked. My first choice was Bard High School Early College. They required me to do essays on humanities and STEM [to apply]. Elyse [BEAM’s Enrichment Coordinator] was very helpful in this process. She helped me review my essays and gave me feedback on what to change and what to add. I am very pleased to say that I got into my first choice. I am very grateful for BEAM’s support. I felt very happy and delighted when I got my results. When applying I was very nervous but at the same time felt confident because BEAM helped me in the process.

”

Brandon is looking forward to attending Bard High School Early College Queens in the fall, where he hopes to play on the basketball team.

Way to go BEAM 8th graders! We’re incredibly proud of you. <3

Want to learn more? Check out this article in Chalkbeat featuring BEAM 8th grader Nevaeha Giscombe, and BEAM’s own Elyse Mitchell.

Here’s a complete list of high schools admissions for BEAM students to date:*

A. Philip Randolph Campus High School (2)

Academy of Software Engineering

Academy of American Studies (2)

Art and Design High School

Aviation Career & Technical Education High School

Bard High School Early College (7)

The Beacon School (2)

Bedford Academy High School

Benjamin Banneker Academy

Benjamin N. Cardozo High School

Bronx Early College Academy

Brooklyn Secondary School for Collaborative Studies

Central Park East High School (4)

Civic Leadership Academy

Coney Island Prep

East Side Community High School (2)

Eleanor Roosevelt High School

Energy Tech High School

Fannie Lou Hamer Freedom High School

Francis Lewis High School

Frederick Douglas Academy

Frederick Douglass Academy VI High School

High School of Economics and Finance (2)

Hostos-Lincoln Academy of Science

Leaders High School

Manhattan Center for Science and Mathematics (6)

Midwood High School (5)

Millennium Brooklyn High School (2)

Millennium High School

Morris Academy for Collaborative Studies

NYC Lab School for Collaborative Studies

NYC Museum School

Park East High School (3)

Pathways in Technology Early College High School

Science, Technology and Research Early College High School

Thurgood Marshall Academy for Learning and Social Change

Townsend Harris High School (3)

University Heights High School (7)

The Urban Assembly School for Law and Justice

Urban Assembly Maker Academy

Washington Heights Expeditionary Learning School

Williamsburg High School for Architecture and Design

Young Women's Leadership School of Brooklyn

BEAM students also received admissions offers from the following Specialized High Schools:

Bronx High School of Science

Brooklyn Latin

Brooklyn Technical High School (4)

Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts

High School for Math, Science and Engineering at City College

High School of American Studies at Lehman College (2)

Queens High School for the Sciences at York College

Stuyvesant

Students admitted to Specialized High Schools will choose between these schools and other admissions offers they received.

We are incredibly proud of our students!

Ange was admitted to Beacon High School.

Brandon was admitted to Brooklyn Technical High School.

Estefani was admitted to Midwood High School.

Mansour was admitted to Bard High School Early College.

Yeshua was admitted to Central Park East High School.

Precious was admitted to Manhattan Center for Science and Mathematics.

Yasong was admitted to Townsend Harris High School.

*We say to date because every year a few BEAM students are under-matched in this process. We are currently working with students who were not admitted to high schools that meet our standards to make sure that they can navigate the appeals process and find a good fit for the next four years.

Race and Identity in BEAM's Workplace

This spring, BEAM’s 20-person staff sat down together for four conversations on Race & Identity at BEAM, where the main focus was getting staff more comfortable with discussing race at work to both grow our capacity to support each other as coworkers and then also serve our students and our mission even better in the future.

The series was the brainchild of Ayinde Alleyne, BEAM’s College Support Coordinator, who would humbly say that he appreciated the help of other staff in designing the series, in facilitating breakout sessions, and in being brave enough to engage in such important conversations at work. But his coworkers want this recap to be a thank you to him, so we’re focusing on his contributions today.

This spring, BEAM’s 20-person staff sat down together for four conversations on Race & Identity at BEAM, where the main focus was getting staff more comfortable with discussing race at work to both grow our capacity to support each other as coworkers and then also serve our students and our mission even better in the future.

Ayinde Alleyne (photo credit: Mike Karsnak)

The series was the brainchild of Ayinde Alleyne, BEAM’s College Support Coordinator, who would humbly say that he appreciated the help of other staff in designing the series, in facilitating breakout sessions, and in being brave enough to engage in such important conversations at work. But his coworkers want this recap to be a thank you to him, so we’re focusing on his contributions today.

Recently, Lynn Cartwright-Punnett, Chief Programs Officer, sat down with Ayinde to ask him more about why he proposed a race and identity series, what the goals were, and what happened. This is a condensed summary of the interview with Ayinde. Throughout the blog post, you’ll also see callout quotes from BEAM staff sharing what they appreciated about the experience of having these conversations.

Why talk about race in the workplace?

“I was able to take language and apply it to how I understand myself, my relationships with coworkers, my relationship to work, and to the work I do at BEAM. It was powerful to have a place during the work day to hold these ideas together.”

I personally talk about race at work because it’s one of the most uncomfortable aspects of life as it relates to work. And it’s also critical at BEAM because while BEAM students and their families interact with many systems of oppression, racial oppression is both the most prominent and the hardest to talk about. I’ve come to believe that the things that are the hardest to talk about are exactly the ones we should discuss.

More recently, I was driven to bring this up as news in our country and across the world kept happening with racial angles and I thought now was the time to do this work to ensure race doesn’t become an elephant in the room that we don’t know how to address.

Why do this with all staff? Why not just have the staff who work directly with students and families be trained to discuss race?

“I think the big thing that sticks with me is just that students won’t feel comfortable coming to us with these questions if we’re not modeling that behavior. And also, not to be afraid of doing something wrong.”

Really, we all tell stories about BEAM’s mission and our students and families, whether that’s in a donor conversation or just at a cocktail party where someone asks you what you do for a living. So I think we all need to know how to talk about our work and our students responsibly. And also, we don’t want to exclude staff if their department isn’t invited to the conversation.

Now, having had the conversations and having had everyone choose to participate fully, our staff really feels unified in a way that we weren’t before. We are all down to name things we notice, to have important conversations that may be awkward. We’re all working together to figure out how to talk about these things. And that staff unity helps the entire organization.

Why is it important to have conversation norms?

Conversation norms are meant to help facilitate effective communication. In daily conversations, when you speak with the people in your life you’re close with, there are norms in place, even if unspoken. Those norms are based on how you know them, how long you've known them, and other dynamics. Those norms happen over time. But at work, formal conversation norms make sense, allowing everyone to be on the same page.

How did you choose the norms for these conversations?

Some of them were chosen based on past experience; things that stuck with me from going to other well-facilitated spaces. But the rest came from listening to staff and hearing what they wanted or needed. I had one-on-one conversations with every staff member before the whole group sessions to ask what was important to them.

“Coming out of the conversations, I’ve reflected a great deal about how I talk about race, and when. . . . Our conversations made me think about how I can bring race up initially in appropriate ways, and how I can dive into conversations deeper when they happen. I know that I sometimes use different language to describe the same ideas as my colleagues, and diving into definitions also helped me understand word choice questions more deeply and how to talk about word choice with others.”

As it happens, one of the norms that mattered the most to me was also one requested by staff: don’t expect perfection from ourselves; be okay with making mistakes in this work. I love this norm because BEAM believes in a growth mindset and that’s true for racial conversations as well. We’re all trying to do the best we can as we also try to be better. We’re just not perfect, but especially in this context, talking about race and oppression, we worry about saying or doing the wrong thing and that having consequences. So the goal was to create a space where we can reduce the feeling of consequences for making a mistake, knowing that making a mistake is a thing we will all do! The risk is when people are afraid of saying the wrong thing, they say nothing and that is really counterproductive. Being a Black man, I wanted to be sure that I could also portray that there are mistakes I make. And when I think of the mistakes I make, I tend to think of gendered mistakes more than racial ones so I had to dig deep to share the ways I’ve made mistakes in racial conversations.

You can see the full list of norms Ayinde developed at the end of this blog post.

Why were the breakout groups so important? How did you design that setup?

“I was blown away by how well the reading and listening materials supported the conversation, how the persistent conversation groups allowed comfort to develop to allow us to address topics, and how the conversation topics were founded in theory but didn’t lead to conversations that were strictly theoretical. ”

Each staff member was assigned to a consistent breakout group for all four meetings. The breakout groups were necessary for two reasons. First, they gave a smaller group space to have detailed conversations you can’t have with 20 people. With five people, you can have complicated and complex discussions, allowing everyone to speak in less time. Second, that team of people was able to build a bond of trust and deeper vulnerability. This happened both because the group worked together over all four sessions but also because groups were designed carefully to ensure no managers were in the room with their team members, that each group represented a mix of departments and demographics.

What’s one piece of advice you would give to someone trying to get more comfortable talking about race, especially at work?

It’s tough! It’s good to start just with definitions, like defining the role race plays in people’s lives. Can you see how race impacts you personally, but also how it impacts society?

“My biggest concern was not saying the right thing. However I was aware that this was not a matter of being right or wrong and the norms established were that it would be a non-judgemental space.”

One of the hardest things to do when starting a conversation about race is to know where everyone is coming from and the only way to know what people are thinking is to ask them. If you can make a space that allows people to open up that part of their thoughts, just get in the habit of talking about it.

If, on the other hand, you’re someone already very aware of the race in society, then the advice is two parts. First, it’s still valuable to take that time to reflect on the ways race has a specific meaning to you at work. Sometimes the structure of talking about race leads to a lot of generalization. And it’s very hard to get away from generalization and to instead talk about what is happening here, especially if it’s personal. Then, once you understand the effect of race on yourself, try to take a step further to understand the effect of race on others.

“I really appreciate the thoughtfulness [Ayinde] put into making sure to understand where everyone was coming from and what our comfort was in having group conversations on race, especially the initial one on one conversations. That space allowed me to be really open and honest in a way that I wouldn’t have been in a big group and be reflective of how that impacts what I’m carrying into the conversation.”

If you’re looking to grow your own thinking and get more comfortable talking about race, here are some resources Ayinde recommended to our team over the course of the Race & Identity Series:

A short guide to anti-oppressive meeting facilitation techniques: http://aorta.coop/portfolio_page/anti-oppressive-facilitation/

A 45 min podcast episode from Dr. Brené Brown on shame and accountability: https://brenebrown.com/podcast/brene-on-shame-and-accountability/

A 3 page piece referenced in the podcast by Audre Lorde: https://collectiveliberation.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/Lorde_The_Masters_Tools.pdf

An article on a framework to having conversations about race at work: https://mitsloan.mit.edu/ideas-made-to-matter/a-5-part-framework-talking-about-racism-work

A short piece on tips for talking about race in the environment of a non-profit: https://www.gmafoundations.com/racial-equity-within-nonprofits/

A short blog post on how to talk about racial disparities in the context of structural racism: https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/how-we-should-talk-about-racial-disparities

A short article on the importance of centering student voice and moving cautiously when we want to tell student stories responsibly: https://www.vox.com/2016/5/31/11785864/reach-higher-initiative

An 18 minute TED Talk by Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw on “The Urgency of Intersectionality”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=akOe5-UsQ2o

A blog post from Austin Channing Brown directed at White people wrestling with fear of talking about race: https://austinchanning.substack.com/p/dear-nice-white-people

A short blog post from the NeuroLeadership Institute about how to improve communication across diverse teams: https://neuroleadership.com/your-brain-at-work/biases-shape-communication/

A 5-page worksheet on analyzing White dominant cultural practices and what it looks like to change to different ones: https://www.cacgrants.org/assets/ce/Documents/2019/WhiteDominantCulture.pdf

This worksheet on interrupting microaggressions as you observe them happening: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Rgy2JwHj189bmHOkZmYH5rDEZZP4pTdS/view

Here, also is Ayinde’s note on the term microaggressions: “Personally, I don't love the prefix micro- in the term microaggression. I feel as though the term is built with the person causing the harm in mind, the action seems small and harmless to them and is usually why they believed it was harmless. The person feeling the effect of the action usually doesn't internalize it as small. The term is often used by many people and resources and I use it occasionally, but I did highlight this issue.”

In addition, here is the full list of conversation norms BEAM used for the four chats:

The goal of these norms is to build trust between each other and preserve this as a safe space for our collective growth. To do so, we ask you to:

Be fully present when you are here. Step away if needed.

Don’t expect perfect articulation of ideas from anyone (including yourself).

Make space for other voices, and make space for silence.

Be open to learning and open to taking risks. (Gently) push beyond your comfort zone.

Ask for literacy moments. Ask questions about words/ideas new to you.

Assume positive intent from others, and also take responsibility for impact on others.

Call each other in and not call each other out.

What's said here, stays here. What's learned here, leaves here.

Expect and accept a lack of closure.

Ayinde; thank you so much for everything you do at BEAM, with our students, our families, and, of course, our staff.

... And Now for Some Math

BEAM Los Angeles has started a math team! The goal is for students to have fun doing challenging math problems, but also to be prepared to participate in math competitions once pandemic closures lift. Some weeks students work on a specific math competition, and other weeks they focus on particular kinds of problems that often appear in math competitions, like the one below, which involves a guessing game. See how you do! (And if you like this sort of challenge, you should also check out this problem from last summer's newsletter.)

You may have played this game before: I am thinking of a number between 1 and 1000; try to guess my number in as few guesses as possible. Each time you guess, I will tell you whether my number is greater than or less than your guess. What is the best strategy so that you are guaranteed to find the correct number with as few guesses as possible?

In this case, the answer is fairly straight forward and not too difficult.

But what if we add a twist: You are allowed to say three numbers in each guess, and I will tell you whether my number is greater than or less than each. Now what is the optimal strategy to find the correct answer in as few guesses as possible? What if instead, I let you ask three yes/no questions each time? Would you use the same strategy?

Let's start with our initial question. If you want to guess a number from 1-1000 in as few guesses as possible and you can make one guess at a time, what's the best way to do it?

One way to think about this is that when you guess a number, call it x, you turn your original problem (searching for a number 1-1000) into a smaller problem: either searching 1-(x-1) or (x+1)-1000. If one of these ranges is too big, and we get unlucky and our number is in that larger range, then we will have more guesses to do! Hence, a good strategy is to always divide the range in half (or as close in half as we can). That way, no matter which half we end up in, the worst case is under control.

Hence, the first time you'd guess 500. If you're over, then you need to check 1-499; if you're under, you need to check 501-1000. (You could also have guessed 501, in which case you'd get ranges that are the same size.) Keep splitting in half. In total, it will take you no more than ten guesses.

In fact, it turns out that 10 guesses is enough to go higher than 1000. One way to look at this is by building up from smaller values. To guess a number 1-3 requires two guesses (your first guess would be 2, and then you might need to guess either 1 or 3 depending on if you were over or under). To guess a number 1-7 thus requires three guesses: start by guessing 4, and then you're left with two ranges of size three (1-3 or 5-7), which you know you can do in two guesses no matter which range it turns out to be. Guessing a number 1-15 requires four guesses (guess 8, and now you've reduced to a range of size 7 which you can do in three more guesses); 1-31 requires five; and so forth.

Notice the nice pattern: with n guesses, you can do a range of size 2n-1. That makes sense, because each guess basically lets you double the range you can check. So with 10 guesses, you could do 210-1 = 1023 numbers. This search strategy is called binary search and comes up all the time in computer science.

Sidebar: Extra credit: This also exposes a neat pattern: if you double one less than a power of two and then add 1, you get one less than the next power of two. Written with an equation, that's 2(2n-1)+1 = 2n+1-1.

So what happens when we get to name three numbers at a time? When we only guessed one number, it would split our range into two subranges (less than or greater than the number we guessed). Now, knowing if the target is greater or smaller than each of three numbers splits our original range into four subranges. We might be smaller than all three numbers, between the lowest and the next two, between the lowest two and the highest, or above the highest.

Effectively, this allows us to take two steps at once: instead of guessing just the number in the middle, we can guess the number in the middle and the number in the middle of both of the possible resulting ranges. Thus, instead of needing 10 guesses, we only need 5 guesses.

This might be surprising. After all, you're guessing three times as many numbers; maybe you would have expected to only need a third as many rounds of guessing. However, because you have to pick all three at first (without knowing the answer to your first guess), you can't do quite as well.

Sidebar: Extra credit: We can also build things recursively like before. We can do 1-3 in one round by just guessing 1, 2, and 3; we can do 1-15 in two rounds by guessing 4, 8, 12 — the resulting range is going to be of size 3, so we can finish it off next round. And so on. The next step would be 15x4 (the four ranges) plus 3 (the three numbers you guess) which would be 63. You'd guess 16, 32, and 48, and whatever range the target number was left in would be size 15, which you can now do in two guesses. The relationship here is that 4(4n - 1) + 3 = 4n+1-1.

So, you'd expect the same with asking three yes/no questions, right?

Well, this is the neat part, and why we decided to highlight this problem. With yes/no questions, you have more flexibility than just "is the number too high or too low." Now you can ask questions whose answers are actually independent of each other, and truly cut your search space in half with each guess. (As an example of two independent questions, you could ask: "Is the number bigger than 500?" and "Is the number even?" Both answers cut your search space in half no matter what order you ask them in.)

So how can we come up with three questions that are all independent of each other? That's actually not too hard if you know binary numbers. For example, written in binary, the number 953 is 1110111001, because 953 = 29 + 28 + 27 + 25 + 24 + 23 + 20 — a power of 2 for each place there's a 1. To turn these into questions, just ask:

Is the units digit in binary a 1?

Is the 2's digit in binary a 1?

Is the 4's digit in binary a 1?

Is the 8's digit in binary a 1?

...

Is the 512's digit in binary a 1?

In total, that's 10 questions you need to ask, one for each binary digit, and then you know the number. That means we have to do four rounds in total. Three questions in each of the first three rounds, and then one more question to finally know the number. But now that we have arbitrary yes/no questions, it really does mean we only need a third as many rounds (rounding up).

What We're Reading

Supermath: The Power of Numbers for Good and Evil

by Anna Weltman

“Math is, at its core, problem solving,” writes Anna Weltman.

But, she admits, if your experience of math all happened in a classroom, this might sound a little hollow. Math problems in school often don’t seem like real problems, at least not problems we really care about answering. (A problem, notes Weltman, is not “an exercise in using a technique that someone taught us.”)

School math can feel pretty disconnected from, say, showing that our electoral system is unfair, or figuring out what symbols on an ancient tablet represent. But math can solve these problems, says Weltman. In fact, math can solve a lot of problems that might seem more cultural than mathematical, because math (like anthropology or sociology or science) is a cultural practice, a practice that can shift and change as cultures change; just ask the Oksapmin of Papua New Guinea.

In Supermath, Weltman takes on incredibly diverse topics, from Incan Khipu (and the Oksapmin of Papua New Guinea) to a perfect-checker-playing computer named Chinook to the Optimal Stopping Algorithm and Twin Primes Conjecture. If this is beginning to sound a bit intimidating to you, don’t worry; Weltman presents sophisticated concepts in clear and understandable language.

[Full disclosure: Another topic that Weltman writes about is our organization, BEAM. We’d recommend the book even if BEAM wasn’t part of it, but we are, so we thought you should know.]

Weltman’s point is not that math can solve everything, or even that math is always used for good (thus the “evil” in her title). Take Weltman’s example of setting bail. Algorithms can (and do) decide how bail is set in some places; but when designing algorithms to make such complex decisions, it’s incredibly difficult to account for all the criteria you (should) care about. Too often the outcome is an algorithm that is biased, even if unintentionally so — this has been proven to be true in the case of bail — because humans write algorithms and humans have biases.

Algorithms can also be biased by design. Think about voting districts. Algorithms are very efficient at drawing gerrymandered voting districts. It turns out, in fact, that drawing districts that everyone thinks of as fair is much harder than drawing districts that are clearly not fair. But proving that an algorithm is unfair turns out to be pretty hard; it takes an algorithm to expose an unfair algorithm.

How can math do better? One way is by providing more opportunities for those who have been excluded from STEM, and math in particular: people of color and women. Weltman notes that this is much more than an academic problem. When people of color and women are shut out of math they miss out on the opportunity to join a prestigious and lucrative field. They are denied opportunities to solve problems that affect their communities. When whole groups, like people of color, aren’t adequately represented among problem solvers, inequities are much more likely to result.

One answer to How can math do better, then, is that math can open its doors to underrepresented groups. But what does it take to become a professional mathematician? A lot more than doing well in school math, at least for a lot of mathematicians.

Many mathematicians grow up with a whole math ecosystem around them. They may have a mathematician in the family; they almost certainly have adults in their lives to help them navigate the world of math camps and teams and competitions. They may be encouraged to learn advanced math concepts starting at a young age. They often see others who look like them in this mathy world, giving them a sense that they belong.

For those who don’t see themselves reflected in this world, math can seem like a pretty foreign and unwelcoming place.

This, writes Weltman, is where organizations like BEAM step in. BEAM both provides opportunities, through summer programs in advanced math, and also connects students to other opportunities, like other summer STEM programs, good-fit high schools and colleges, internships, and ultimately, jobs.

BEAM also helps students build a rich community with their mathy peers. Finally, BEAM helps students develop their own voices to push the culture of mathematics to accept them and to value them for who they are.

Weltman closes her book with the unlikely story of Marjorie Rice, who in 1975 at her kitchen table discovered a new type of pentagon that could tile flat space. She was a 52-year-old “housewife” with one high school math course under her belt. Yet she found something no one had found before. Was it an earth-shaking discovery? No, writes Weltman, but it was a beautiful piece of math. “Even more importantly, this beautiful piece of math had the power to change Rice’s life.” And that, concludes Weltman, is a superpower.

“The power of mathematics,” concludes Weltman, “comes in part from the problems it solves. But the mathematicians, likely and unlikely, are ones who wield it. Math would have no power without them. Let’s distribute that power widely and see what people do with it.”

College Decision Day: Congratulations BEAM Seniors!

During times of change and stress, it takes courage to make big decisions. Last spring, our high school seniors stepped up to the challenge as they navigated college decisions this year. We're proud to announce the schools our students will be attending.

During times of change and stress, it takes courage to make big decisions. Our high school seniors are stepping up to the challenge as they navigate college decisions this year. We are so proud of all the BEAM students who are starting college in the fall!

We're pleased to announce the schools that the following students will be attending:

Images from left to right display: Danielys (Yale), Angel (DePauw), Akriti (Stanford), Grace (Sophie Davis/CUNY School of Medicine), Iovanni (University of Chicago), María (Columbia), Nasheily (Fordham), Savva (Stevens Institute of Technology), Komila (Union), Tchaas (University at Buffalo).

In addition to the students pictured above, we want to congratulate all our graduating seniors. Here's a list of BEAM students currently ready to announce their college decisions:

Agata, Wesleyan University

Akriti, Stanford University

Alejandro, Lehigh University

Alex, Long Island University

Angel, DePauw University

Arianna, State University of New York at Buffalo

Bryant, The City College of New York

Danielys, Yale University

Dan, State University of New York at Stony Brook

Deja, Brooklyn College

Lance, The City College of New York

Gabriela, Union College

Grace, The City College of New York

Ilona, Cooper Union

Iovanni, University of Chicago

Jacob, The City College of New York

Jessica, The College of Staten Island

Komila, Union College

Lizbeth, Skidmore College

Luis, Columbia University

Luis, Cooper Union

Maria, Columbia University

Mariam, Bard College

Milani, Cornell University

Nasheily, Fordham University

Nyasia, Sarah Lawrence College

Racquel Baldeo, Colgate University

Savva, Stevens Institute of Technology

Tchaas, State University of New York at Buffalo

Xavier, Cornell University

BEAM students were also awarded many scholarships and other forms of financial aid:

Akriti, Danielys, Iovanni, and Luis were selected to be part of the QuestBridge National College Match Program, which provides a full-ride scholarship through college to students who are accepted at one of the program’s partnering schools.

Luis was awarded a Gates Scholarship, which provides funding for the full cost of attendance that is not already covered by other financial aid and the expected family contribution.

Angel was named a Posse Scholar in recognition of outstanding leadership potential. Posse Scholars receive full-tuition scholarships.

Deja earned a spot at Macaulay Honors College of the City University of New York; promising students receive academic and financial support to realize their leadership potential and graduate debt free.

Grace was admitted to Sophie Davis Biomedical School/CUNY School of Medicine, which offers a 7-year BS/MD program.

Numerous other students were offered amazing financial aid packages by the colleges they will attend. The aid packages provided by Bowdoin, Columbia, University of Chicago, and Yale are particularly generous, as these schools meet 100% of demonstrated need (without loans). Some scholarships are even generous enough to cover additional expenses that may come up, such as flights to and from home at the start and end of each semester.

Our seniors did an incredible amount of work to get through high school. Congratulations to you all! 11th graders: now it's your turn and BEAM is here for you.

For those following along at home, here is a list of the colleges to which BEAM students were admitted this year:

Adelphi University

Arkansas Baptist College

Babson College

Bard College

Bentley University

Berklee College of Music

Boston University

Bowdoin College

Brandeis University

Case Western Reserve

University

Clark Atlanta University

Colgate University

Columbia University

Concordia University

Connecticut College

Cooper Union for the

Advancement of Science

and Art

Cornell University

CUNY Baruch College

CUNY Borough of

Manhattan Community

College

CUNY Bronx Community

College

CUNY Brooklyn College

CUNY City College

CUNY City Tech

CUNY College of Staten

Island

CUNY Hunter College

CUNY John Jay College of

Criminal Justice

CUNY Kingsborough

Community College

CUNY Lehman College

CUNY Queens College

CUNY School of Medicine

DePauw University

Drexel University

Elizabeth City State

University

Elmira College

Emerson College

Emory University

Fairleigh Dickinson

University

Fordham University

Franklin and Marshall

College

Georgia Institute of

Technology

Gonzaga University

Hamilton College

Harvey Mudd College

Hobart William Smith

Colleges

Howard University

Ithaca College

Jackson State University

Johns Hopkins University

Kalamazoo College

Lehigh University

Lincoln University

Long Island University

MCPHS University

Michigan State University

Middlebury College

Montclair State University

Morgan State University

Mount Holyoke College

New York Institute of

Technology

Norfolk State University

Northeastern University

New York University

PACE University

Pennsylvania State University

Quinnipiac University

Rensselaer Polytechnic

Institute

Rice University

Rochester Institute of

Technology

Roger Williams University

Rutgers University

Sarah Lawrence College

Savannah College of Art and

Design

Siena College

Skidmore College

Stanford University

Stevens Institute of Technology

St John’s University

St Lawrence University

SUNY at Albany

SUNY at Binghamton

SUNY at Geneseo

SUNY at New Paltz

SUNY at Purchase College

SUNY at Old Westbury

SUNY at Oswego

SUNY Buffalo State

SUNY College of

Environmental Science

and Forestry

SUNY Cortland

SUNY Oneonta

SUNY Stony Brook

University

SUNY University at Buffalo

Susquehanna University

Syracuse University

Temple University

The College of Saint Rose

Trinity College

Tufts University

Union College

University of Chicago

University of Massachusetts-

Amherst

University of Rhode Island

University of Rochester

University of Wisconsin-

Madison

Wesleyan University

Wheaton College

Worcester Polytechnic

Institute

Yale University

Happy 𝜋 Day!

Happy 𝛑 Day! What better day to celebrate our favorite, familiar, fantastic irrational number? This 𝛑 Day we are bringing you a 𝛑-centric approximation activity, a detailed explanation of why this activity approximates 𝛑, and a special bonus math problem and solution (in case you want to spend your 𝛑 Day doing math, math, and more math :) ).

Happy 𝛑 Day! What better day to celebrate our favorite, familiar, fantastic irrational number? This 𝛑 Day we are bringing you a 𝛑-centric approximation activity, a detailed explanation of why this activity approximates 𝛑, and a special bonus math problem and solution (in case you want to spend your 𝛑 Day doing math, math, and more math :) ).

First, the activity:

Select your favorite straight thin object you don’t mind tossing at random. For example: birthday candles, crayons, toothpicks, Q-tips, etc. The more the merrier.* Whatever you pick, you want them all to be about the same length. We will use birthday candles for our example.

Make parallel lines on a flat surface. Make the distance between the lines twice as far as your throwing object is long. So, for birthday candles, your lines should be two candle lengths apart. To make lines you can use masking tape or Sharpie on butcher paper.

Now toss all your throwing objects onto the flat, lined surface. Carefully count how many objects cross a line. Now divide the number of objects you tossed by how many crossed one of the lines. Does this ratio look familiar?

*If you don’t have 100 or more of your tossing objects you may wish to do the experiment multiple times using fewer objects. Just keep a tally of the total number of objects you have tossed and the total number that have crossed a line. And use your tossing object tally and crossing tally to find the ratio at the end.

Why in the world does this work?

First, let's think about our set-up. The lines are two tossing objects apart so from here on our we will just use the length of our tossing object as our units. In our case we were tossing birthday candles, so for our calculations and graphs 1 unit = 1 candle length. Okay, now let's get into calculations. To simplify the problem we’ll start by thinking about just one of our candles, and see if we can work out the probability that it should cross a line when tossed randomly.

Zooming in on just one of our candles we have the following situation. (We included the two candles along the edge just as a reminder that the lines are 2 units apart).

Examining this picture we see that there are two variables, the angle at which the candle falls, θ, and the distance from the center of the candle to the closest line, D. Theta can vary from 0 to 𝛑 degrees and is measured against a line parallel to the lines in the experiment. The distance from the center of the candle to the closest line can never be more than half the distance between the lines, which means D ≤ 1 unit.

The candle in the picture misses the line. We know that candle will hit the line if the closest distance to a line (D) is less than or equal to the length of the dotted line, L. Thanks to trigonometry, we can find the length of this dotted line in terms of θ, and it is ½ (sin(θ)), so L is a function of θ, and we can write L(θ) = ½ sin(θ). If you aren’t familiar with trig functions yet, hang in there, you can still follow most of this! You just have to take our word on the graph of L(θ).)

In the graph below, we plot D along the y-axis and L(θ) along the x-axis. The values on or below the curve represent a hit, namely D ≤ L. The chances that we will hit the line are given by taking the area below the curve (that is the area of values of D and L that yield a hit) and dividing it by the area of the rectangle that represents all possible values for D and L (this rectangle is shown with the dotted green lines).

The area of the rectangle is of course easy to find and it is just 𝛑. The area of the shaded region does require some calculus to find and it is given by the definite integral of L(θ) evaluated from 0 to 𝛑, which comes out to just 1. Which means that the chances a value of (D,θ) randomly chosen fall within the shaded area are 1/𝛑. Which is the same as saying that the chances we hit the line on any given throw are 1/𝛑. That means that if we threw as many candles as we could randomly, about 1/𝛑 of them should hit the line. So:

Which means:

So there we have it, our famous and familiar ratio, 𝛑, showing up in an unusual and unexpected place. This explanation was largely based on this handy overview and explanation of Buffon’s needle problems: https://mste.illinois.edu/activity/buffon/. It also includes a simulation, which is the less messy option for trying this experiment if you don’t have a looooot of tossing objects at home.

And if you’d like to celebrate 𝛑 Day with a little extra math, try out the challenge problem below. (The answer appears after the problem.)

Following BEAM Discovery (our summer program for rising 7th graders), students are sent monthly Challenge Sets, fun math puzzles that students can do independently (and win prizes!). This is a math problem from the first Challenge Set of this school year. (It comes from the Math Kangaroo Contest.)

Myriam chooses a 5-digit whole number, and deletes one of the digits to make a 4-digit number. When she adds the 5-digit and 4-digit numbers together, she gets 52713.

What is the original 5-digit number?

Solution:

Let’s use A, B, C, D, and E to represent the digits of our 5-digit number, where A, B, C, D, E are all whole numbers from 0 to 9. So our 5-digit number looks like ABCDE. If this is the case, then we have 5 options for our 4-digit number: ABCD, ABCE, ABDE, ACDE, and BCDE. You might notice that four of these options end in the same digit as our original 5-digit number, namely E.

Well, what happens when we add two numbers that end in the same digit? In the ones place of our new number we will get the ones digit of E + E = 2E. We know that 2E must be an even number, so its ones digit is 0, 2, 4, 6, or 8. But we are looking for a ones digit of 3, because our 5-digit number and 4-digit number need to sum to 52713. That means we know that we don't want our 4-digit number to end in E. So, in fact, ABCE, ABDE, ACDE, and BCDE aren’t options.

Note: We interrupt our original post to provide an alternate (and really lovely) solution suggested by a BEAM supporter:

Now that we know the last digit is the one that must be dropped, we have an approximate equation X + X/10 ~ 52713. Solving this equation gives X ~ 47920.9090..., from which we can immediately deduce that A = 4, B = 7, C = 9, and D = 2, and very likely E = 1. Testing shows that this is indeed the solution, making short work of this problem!

This clever alternate solution path was submitted by Marc-Paul Lee, a long-time BEAM supporter who, unlike the theoretical mathematician who suggested this problem, knows how to approximate! :-D

And now, back to our original solution:

Now we know that Myriam must have deleted E, the digit in the ones place. So, our 4-digit number must look like ABCD. We also know that ABCDE + ABCD = 52713. We might think at this point that D + E = 3, but remember that just the ones place of D + E needs to be 3, so D + E could equal 3 or 13. We know that 0 <= D + E <= 18 (because D and E are 1-digit numbers so neither of them can be greater than 9) so D + E can’t equal 23, or anything else ending in 3 except 3 or 13.

Moving on to the tens column, we might think that D + C = 1 or 11, but is that right? If D + E > 9, then we will have to carry a 1, which means that D + C might actually be 0 or 10 and we would still get the 1 we need in our tens place. So D + C = 0 or 1 or 10 or 11. In a similar way C + B = 6 or 7 or 16 or 17, and B + A = 1 or 2 or 11 or 12. Finally, we know that A = 4 or A = 5.

Since A > 3, B + A (in the thousands place) can’t equal 1 or 2 (two of our options above). So, B + A = 12 or 11. Which means we carried a 1 to the ten-thousands place and A = 4 not 5.

So B = 8 or B = 7. If B + A = 12, then we didn't carry a 1 when we added C and B, so C + B = 6 or 7, but that’s not right because if B + A = 12, then B = 8. So B + A = 11, which means B = 7.

Now we know A = 4 and B = 7, and B + A = 11, which means we did carry a 1 from adding C and B, so C + B = 16 or 17. Thus, C = 10 or 9, but it can't be 10 because it is a 1-digit number. So C = 9.

Now we know that A = 4, B = 7, and C = 9, and C + B = 16. Because C + B = 16, we know that to get the desired 7 in our hundreds place, we must have carried a 1 from our addition of D and C. So D + C = 11 or 10. But because we know that C = 9, we know that D = 1 or 2, which means that E + D < 12. So E + D = 3, and we know that we didn’t carry 1 from our addition there, which means that D + C is not equal to 10, leaving us with D + C = 11. Plugging in C = 9, we can now find that D = 2 and E = 1.

Putting all the pieces together we get that Myriam’s original number, ABCDE, is 47921. And just to check, let’s do one last step: 47921 + 4792 = 52713.