Welcome to the BEAM Blog!

... And Now for Some Math

At BEAM Discovery the 100 Problem Challenge encourages students to work collaboratively; this past summer students earned a badge for completing a problem from this list of intriguing, puzzle-like problems. We can’t offer you a badge, but this one is pretty satisfying to solve, so give it a whirl!

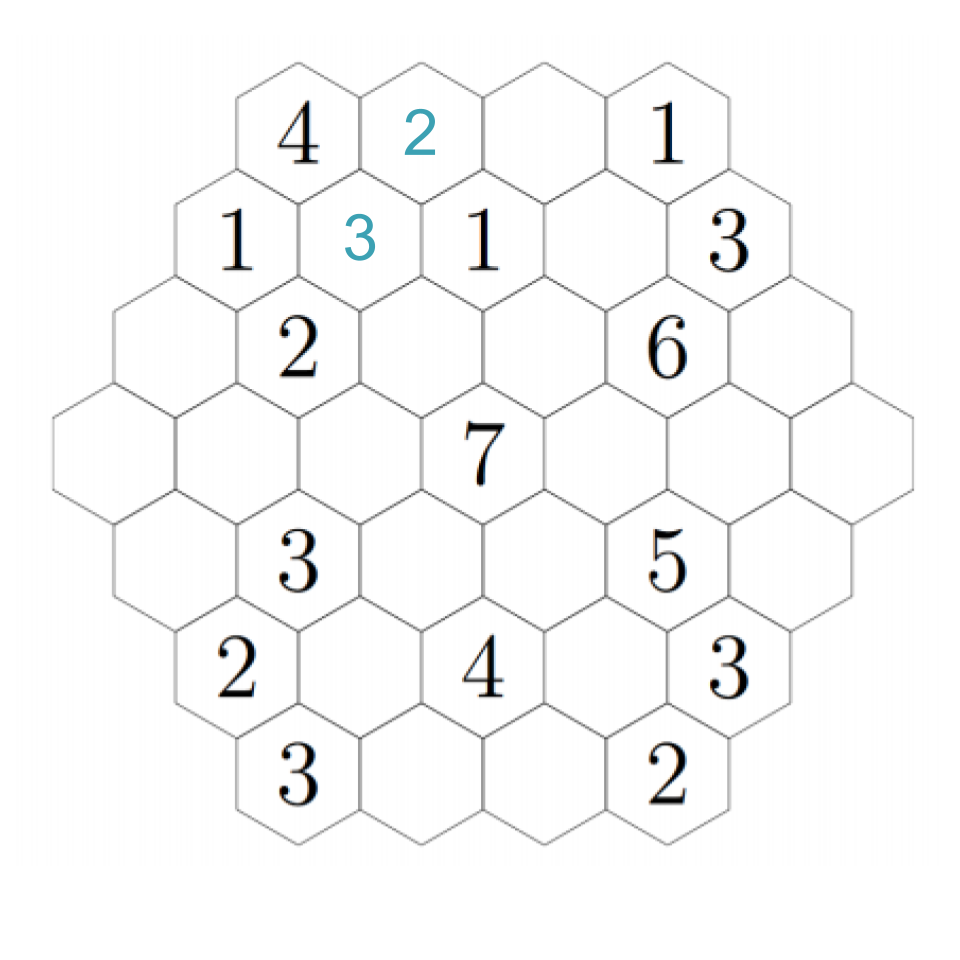

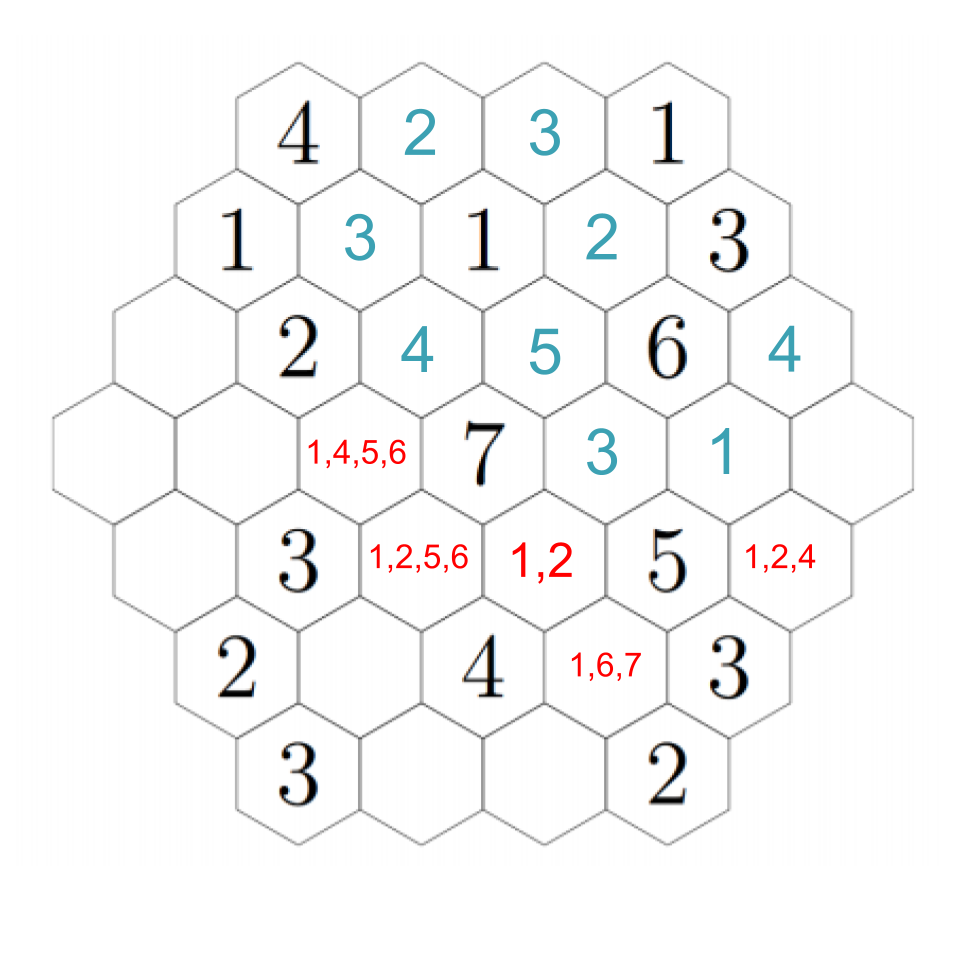

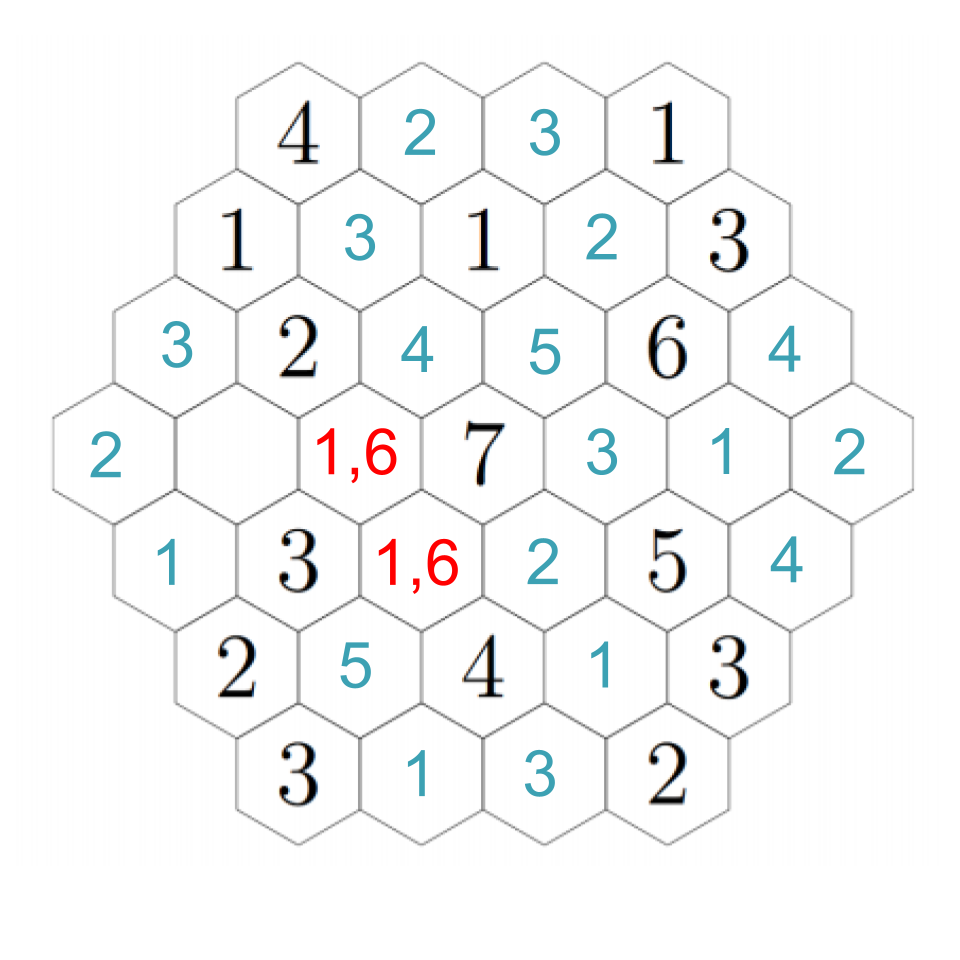

Fill in each of the hexagons below with a positive integer so that the number in each hexagon is equal to the smallest positive integer that does not appear in any of the hexagons that touch it.

At BEAM Discovery, the 100 Problem Challenge encourages students to work collaboratively; this past summer students earned a badge for completing a problem from this list of intriguing, puzzle-like problems. We can’t offer you a badge, but this one is pretty satisfying to solve, so give it a whirl!

Fill in each of the hexagons below with a positive integer so that the number in each hexagon is equal to the smallest positive integer that does not appear in any of the hexagons that touch it.

(Credit for this problem goes to USA Mathematical Talent Search, which, along with BEAM, is part of the Art of Problem Solving Initiative.)

Read on below the figure for the solution.

Solution:

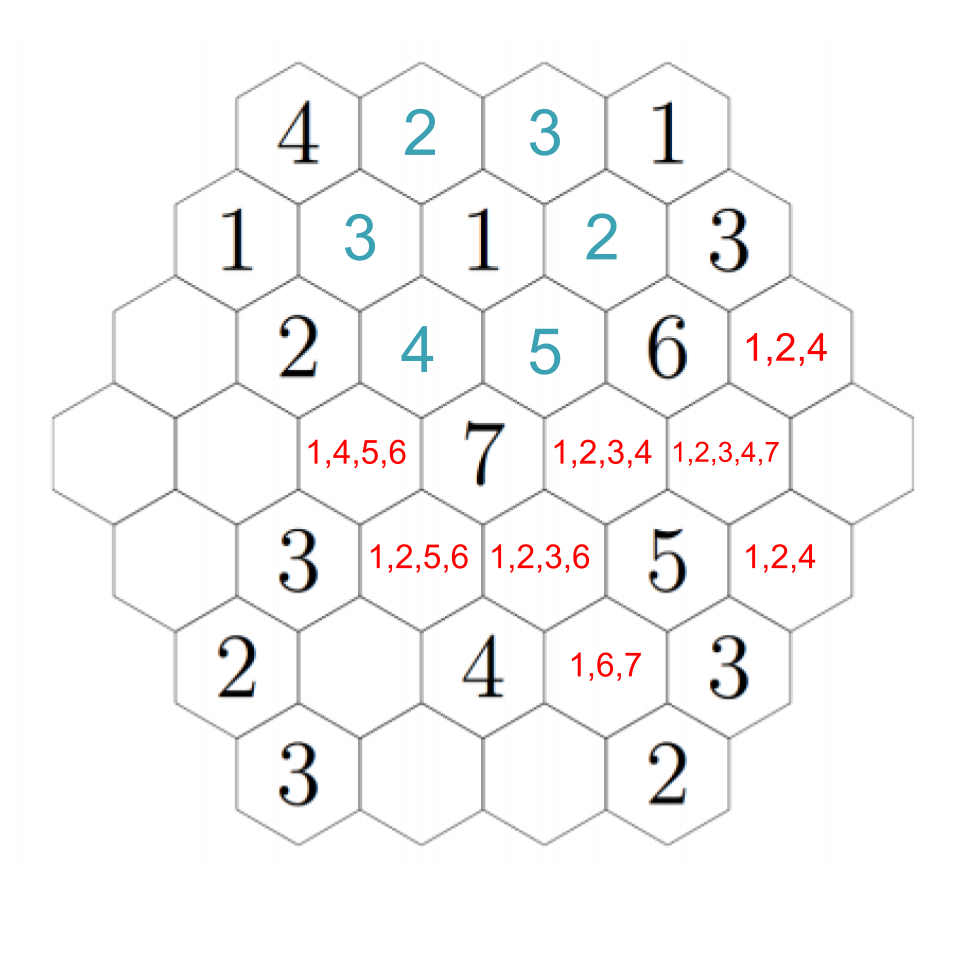

We start by reframing the problem a bit. The problem says the number in each hexagon should be equal to the smallest positive integer that does not appear in any of the hexagons that touch it. Here is another way to say the same thing: each tile must have all of the whole numbers less than its number contained in the adjacent tiles. For example 4 must have 1, 2, and 3 in the tiles surrounding it. Why? Think about it this way: if any of the numbers smaller than 4 weren't in the tiles adjacent, then it wouldn't be the smallest of the numbers that aren't adjacent. If they do all appear then it is, in fact, the smallest of the numbers in adjacent tiles.

So what does that mean? The 7 in the center, for example, has to be surrounded by 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6. But for any of the 1’s in the puzzle, there is no restriction on what is allowed to be by them except that they can’t be adjacent to another 1.

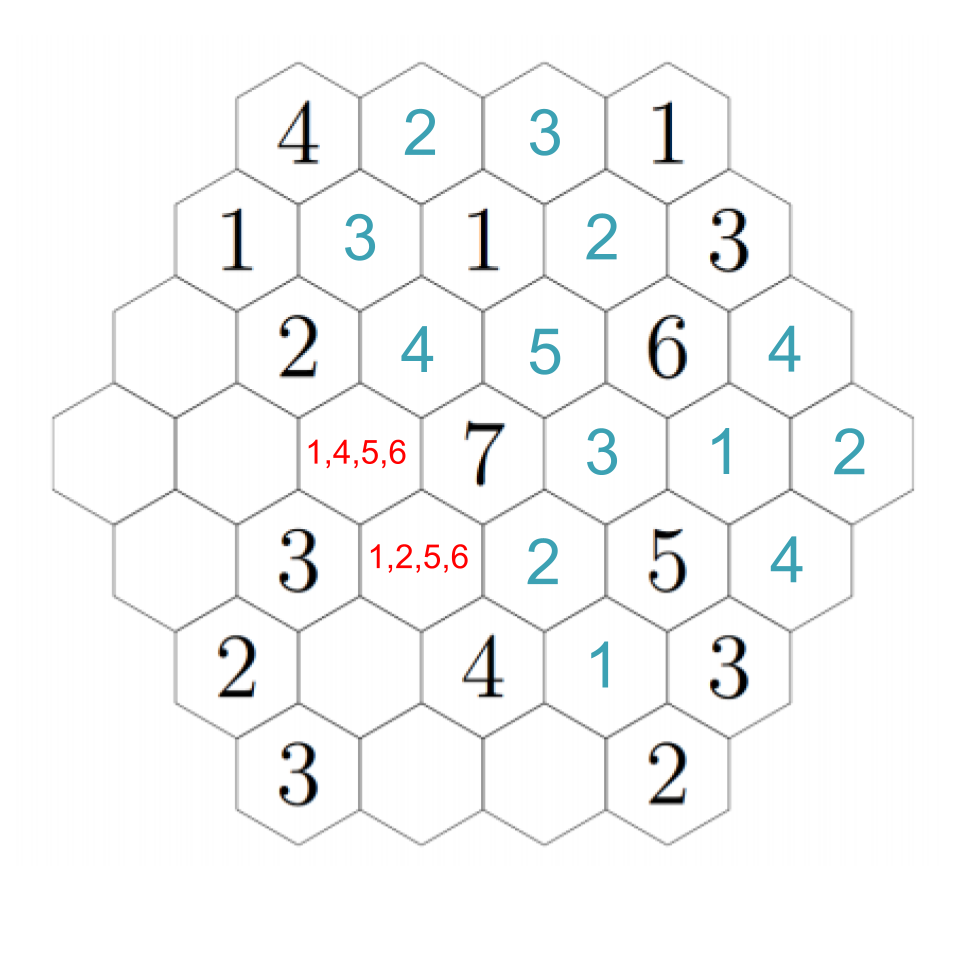

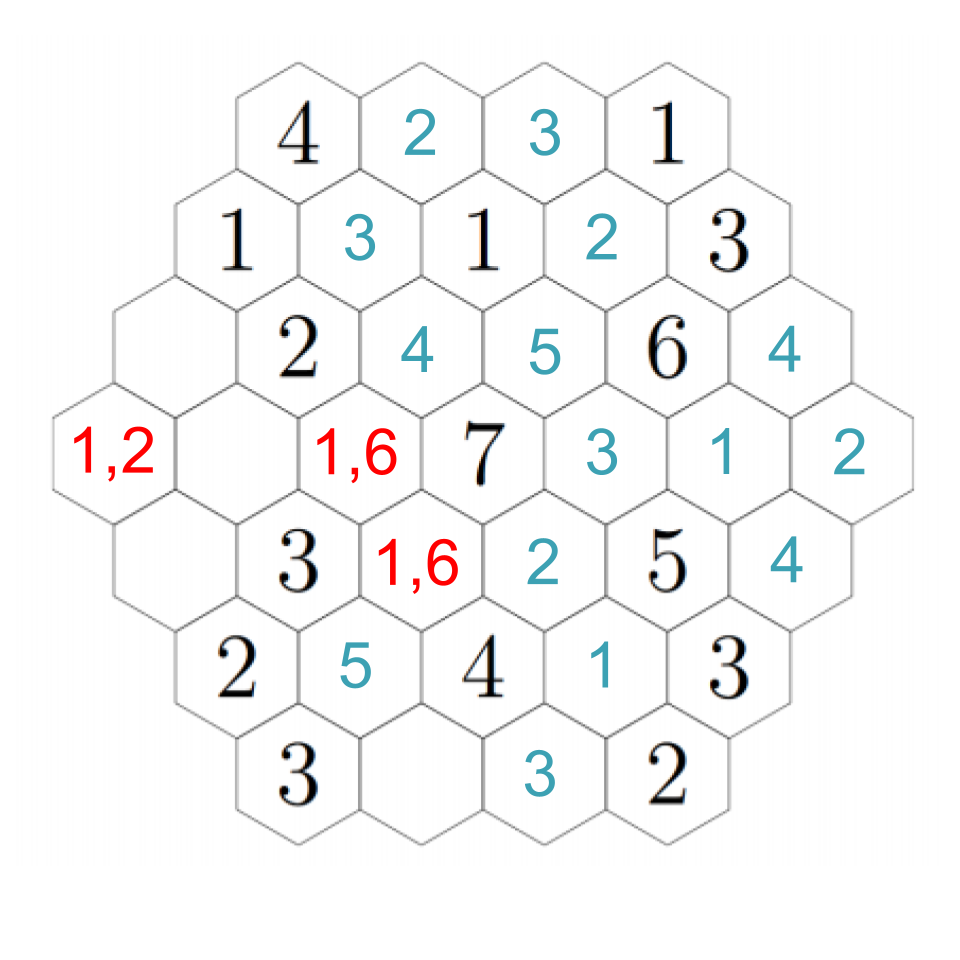

Let's look for any deductions we can make right out of the gate. Start with the four in the upper left: it has three hexes near it, which must be filled with 1, 2, and 3. There's already a 1. The 2 can't appear next to the other 2, so we can fill them in:

Now that you have a flavor for this, see if you can figure out what we might do next. This is going to be a lot more fun to read if you try to anticipate what we'll do!

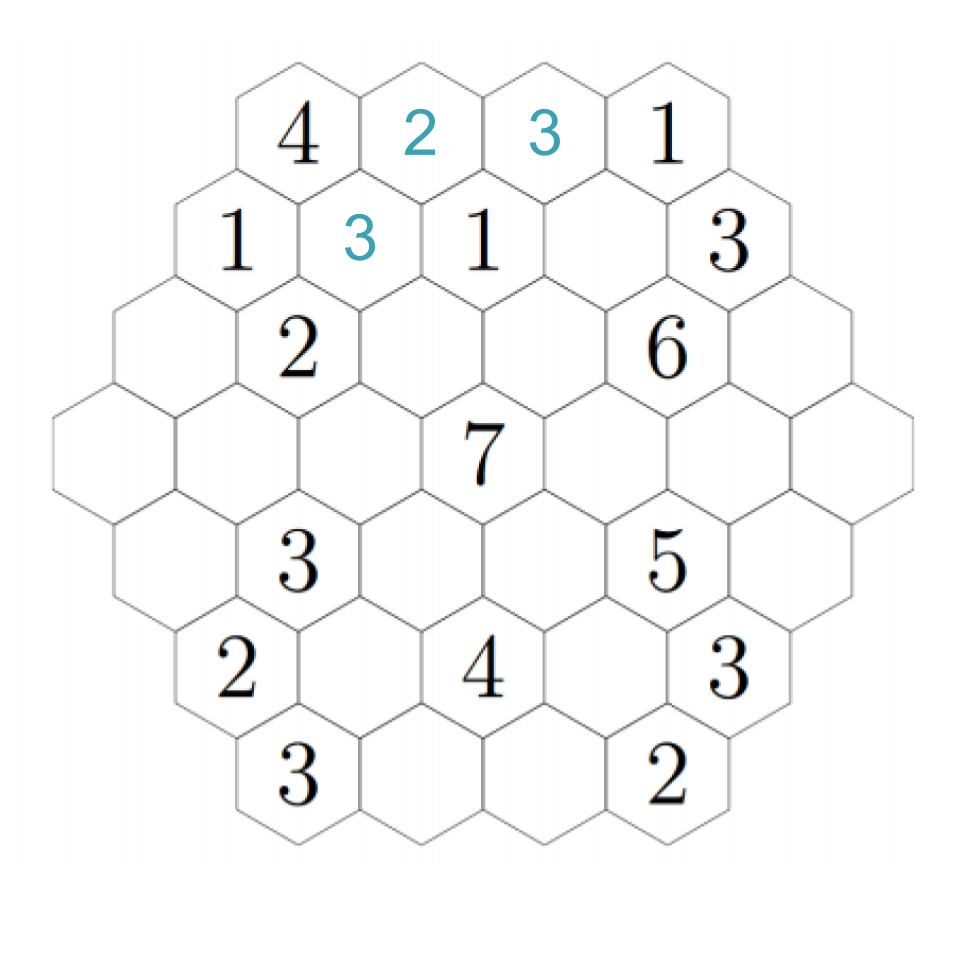

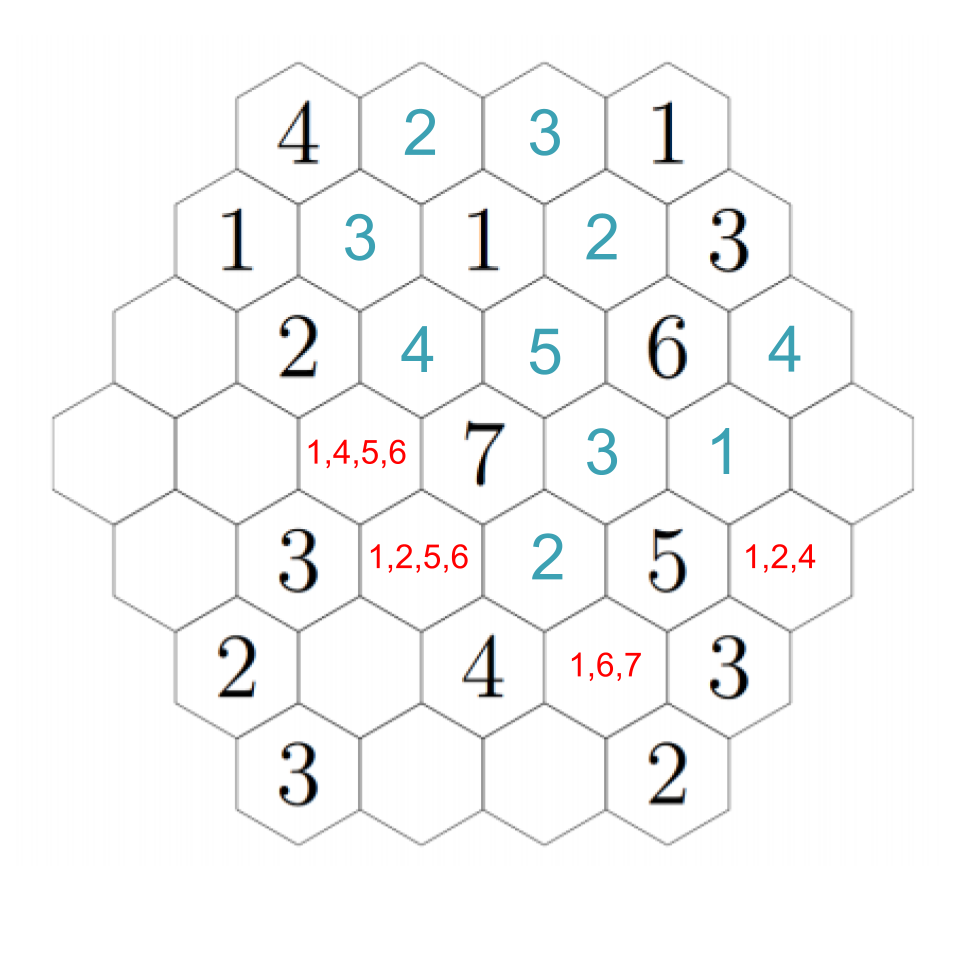

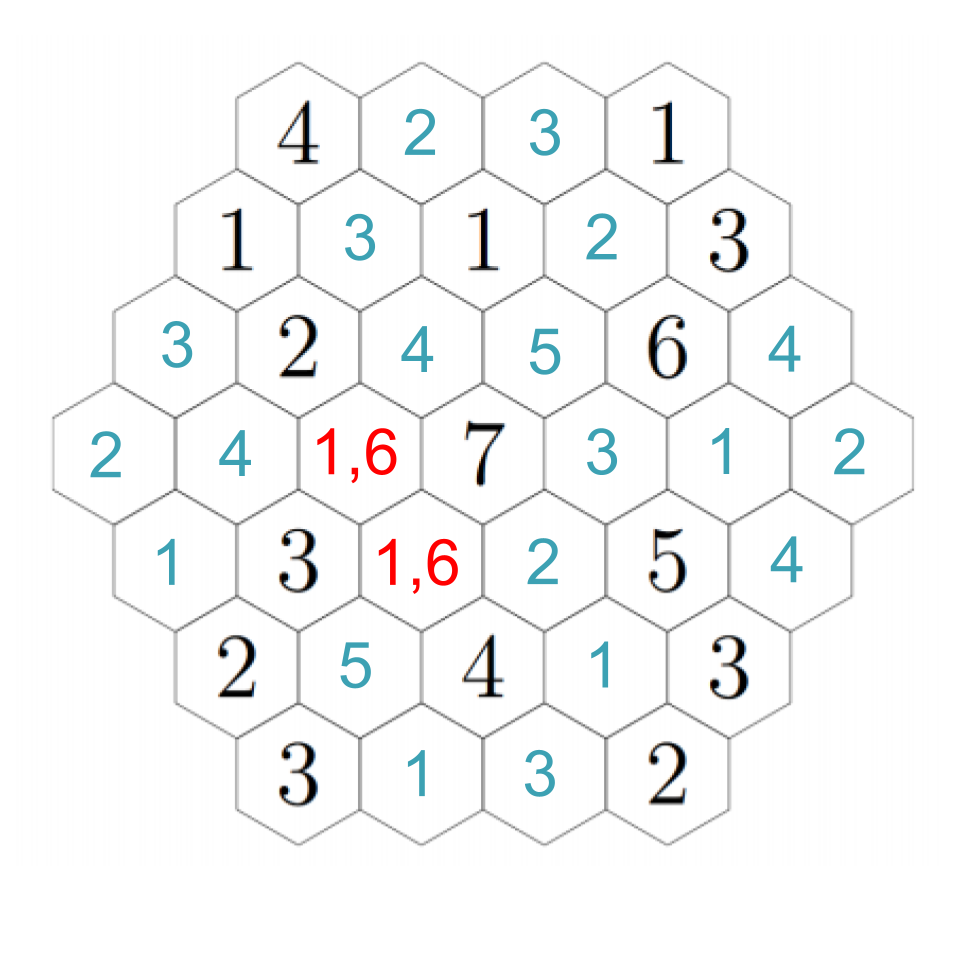

Did you figure it out? Consider the options to the right of the new 2. This hex cannot be a 1 or a 2, because those are adjacent; it cannot be a 4 or higher because there is nowhere nearby to put a 3. Hence, it must be a 3.

That seems to be the last of the clear deductions we can make... or is it? If you're really eagle-eyed, you'll see that there's only one hex next to the 6 that can possibly have a 5 in it, and that's just to its left. Every other hex is either next to a 5, or doesn't have enough free hexes next to it to get it up to five.

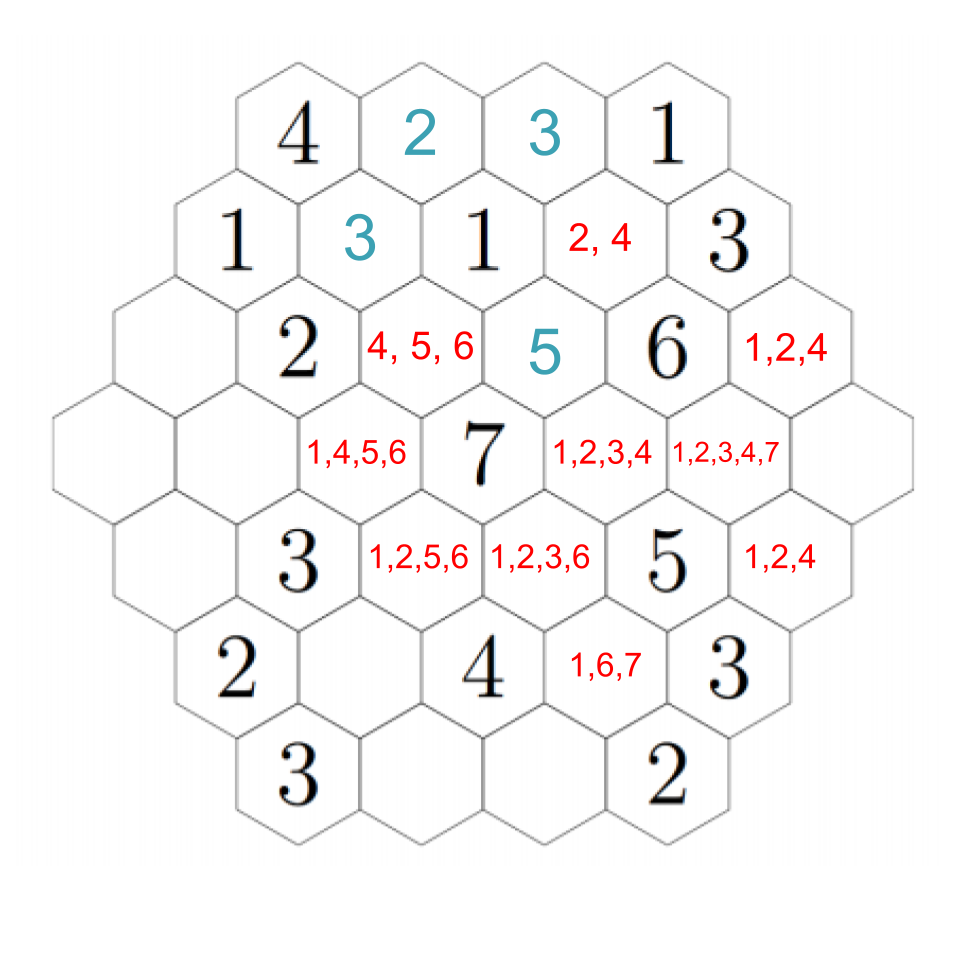

One way to keep track of all that is to write in all the options for the hexes you're considering. That helps you organize your work, something like this:

In the above, we've calculated all possibilities for a few spots, knowing that they can't touch the same number on any edge, and that they must have enough open spaces nearby to get them up to the possible numbers.

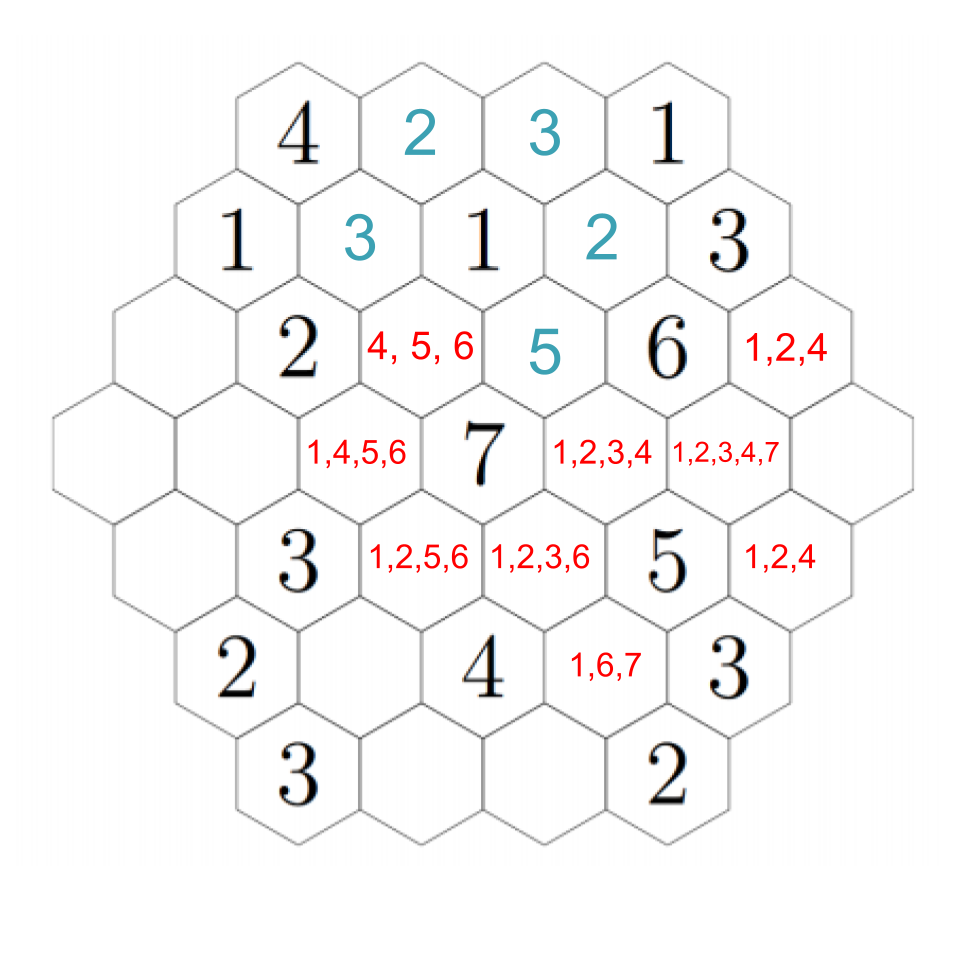

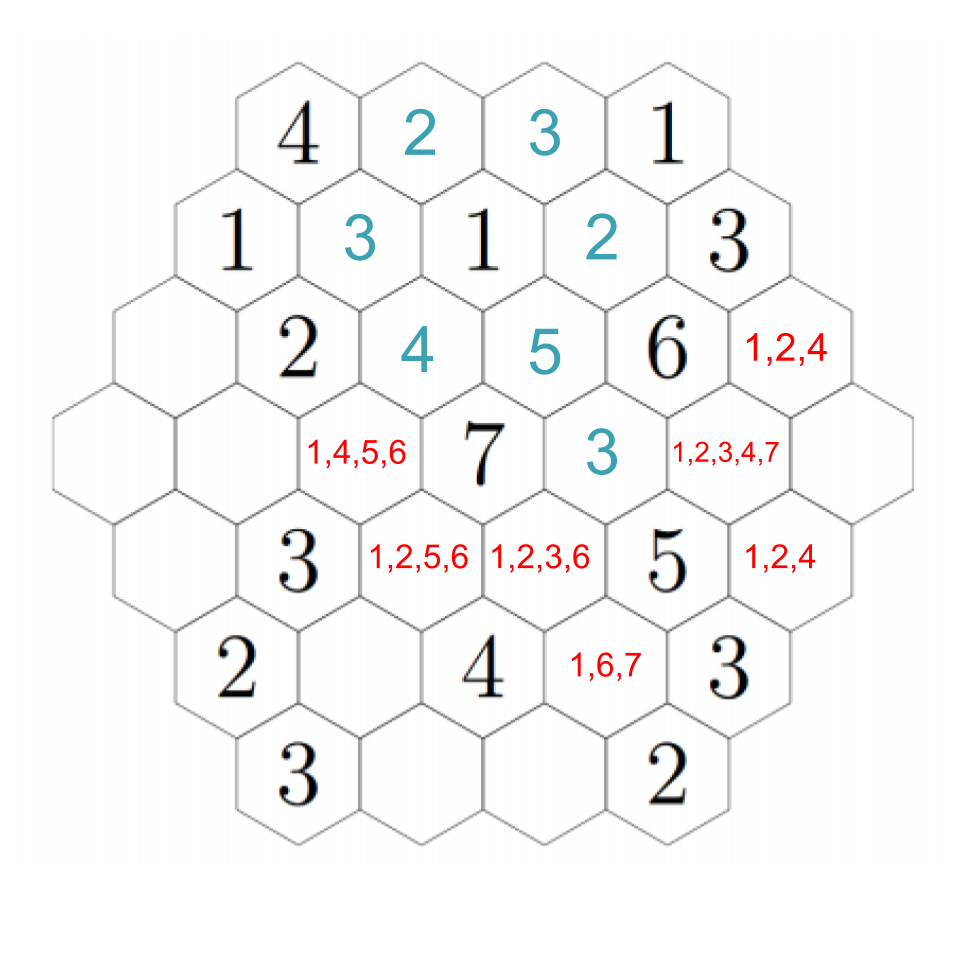

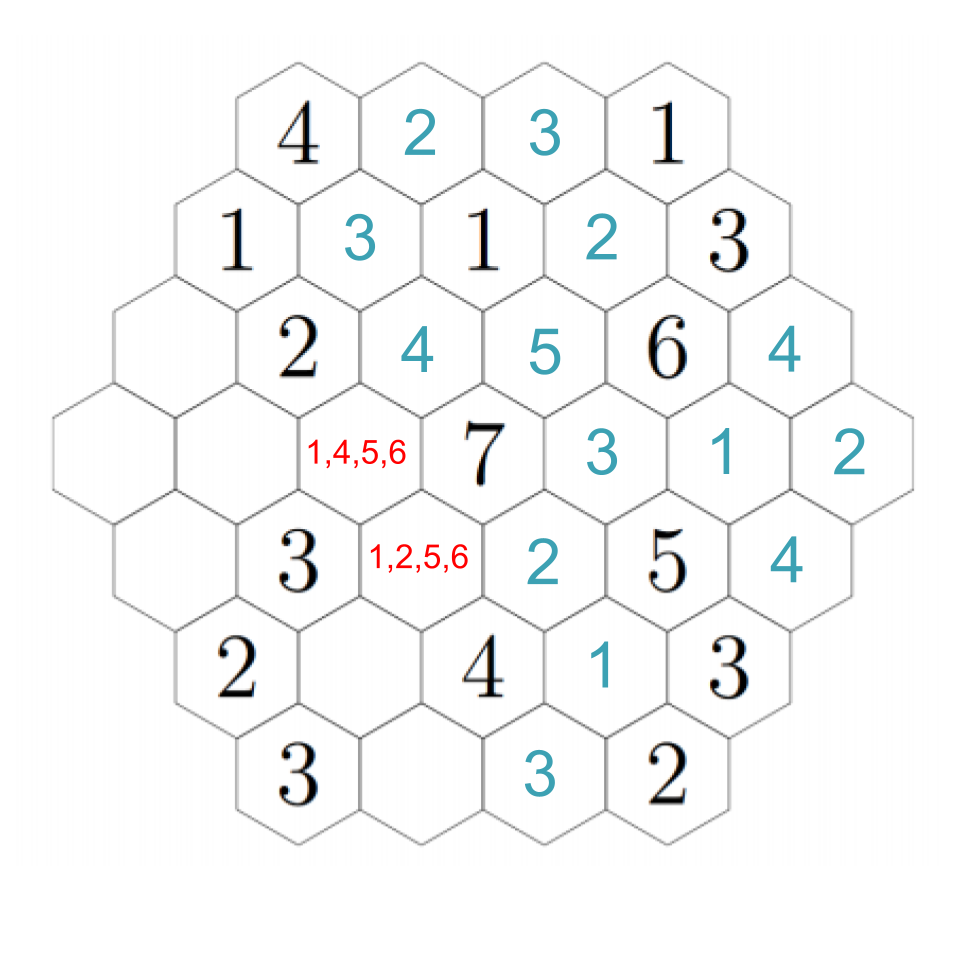

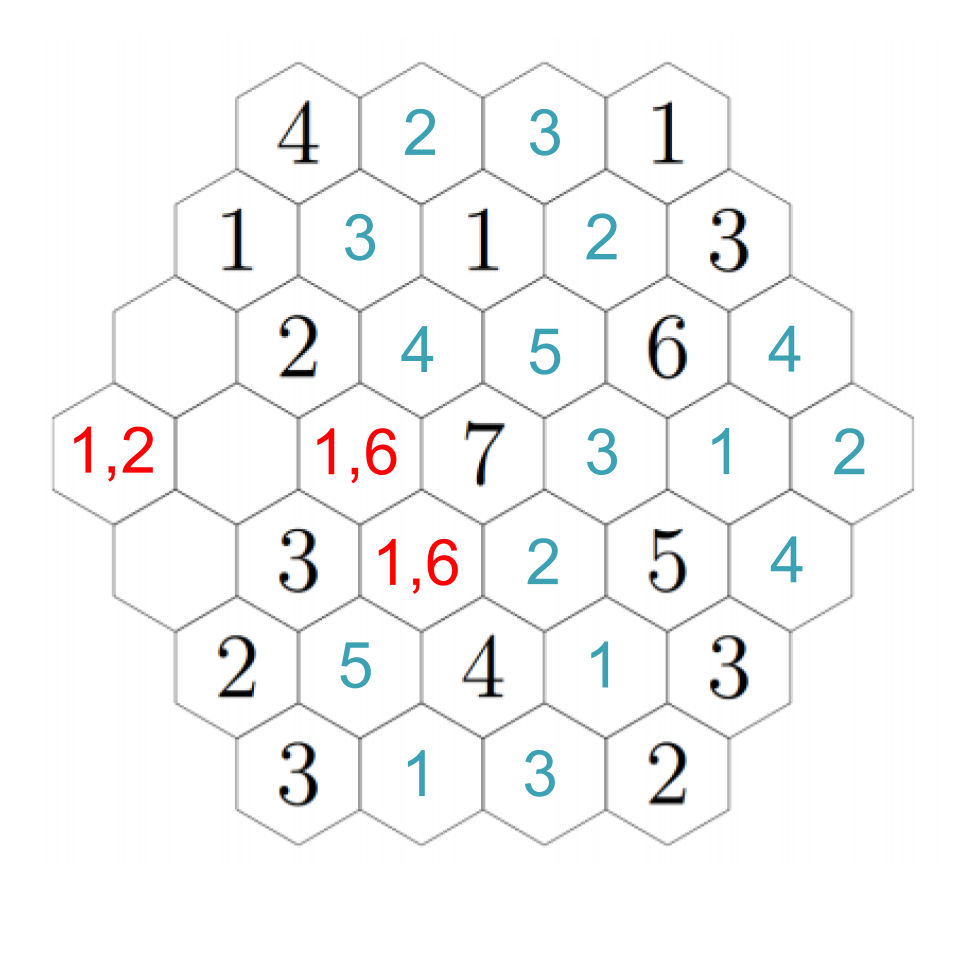

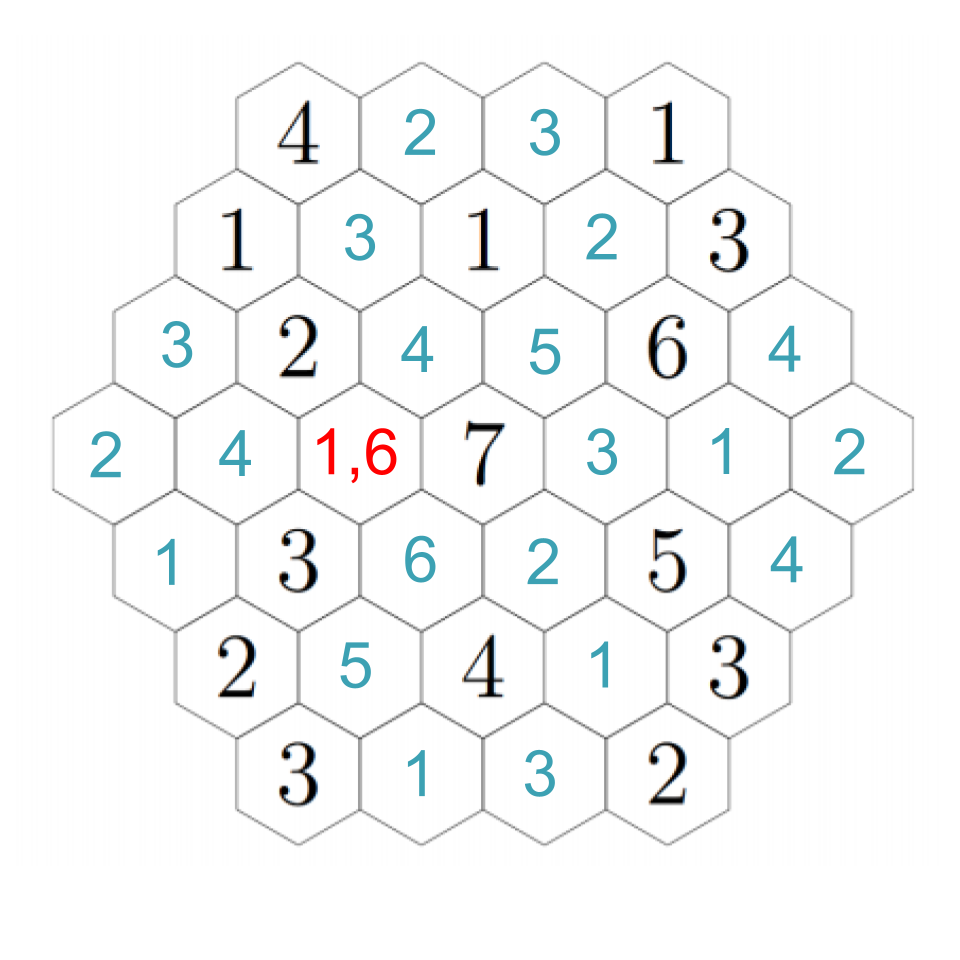

Anyway, back to our puzzle. We must have a 5 adjacent to the 6, but there is only one spot that can support a 5, so that must be the required 5:

Now we can see that above the 5, we must have a 2; the 5 also needs to have a 3 and 4 nearby, and there's only one way to fill those in the remaining two open hexes near it. Click through the images below to follow step-by-step.

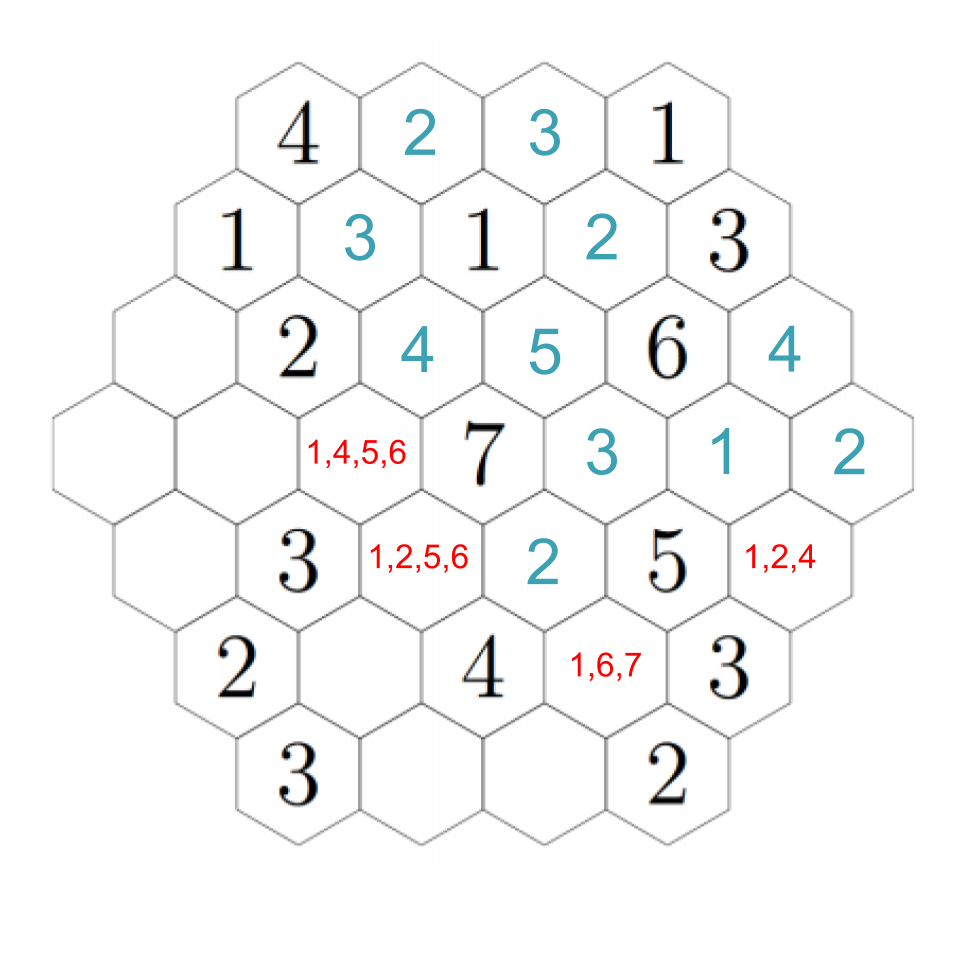

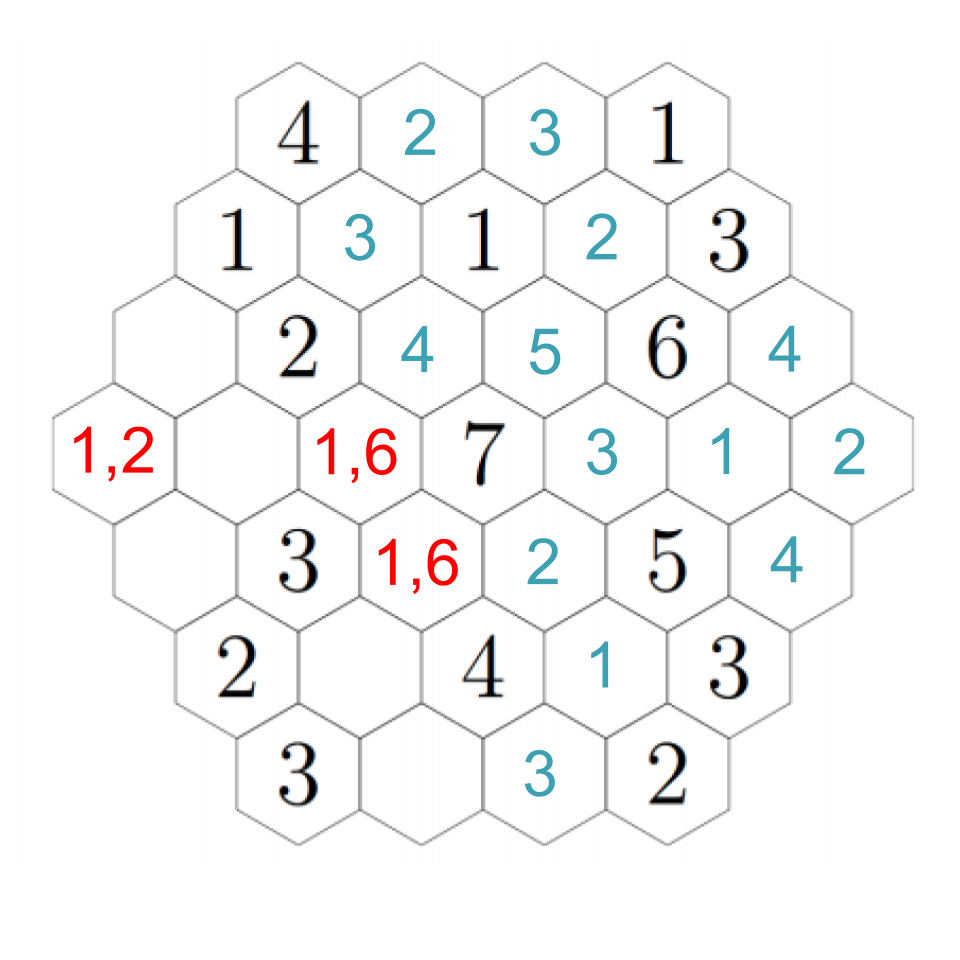

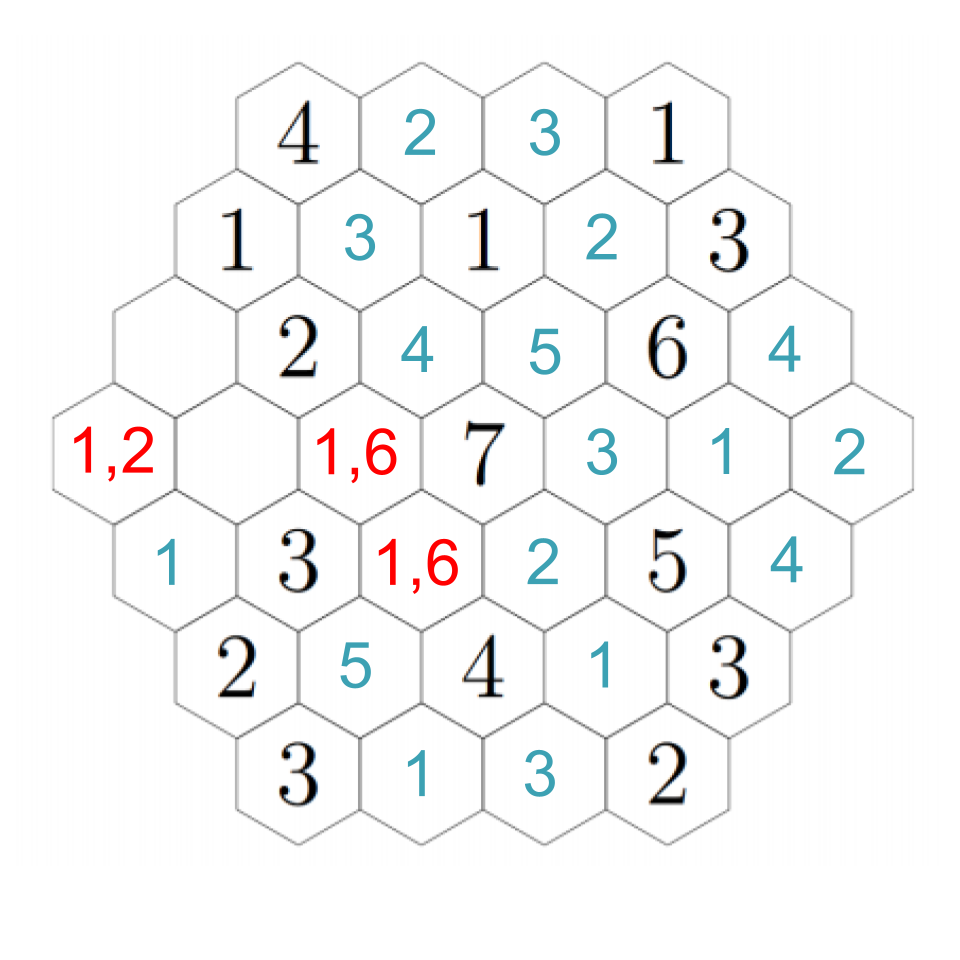

The 3 we just placed needs to have a 1 and 2 adjacent to it, which means the two remaining open hexes must be a 1 and 2 (although we don't know which is which yet). However, that means that the 6 next to the 3 can only have its needed 4 in the hex just to its right, because all the other hexes will be taken. It also needs to have an adjacent 1, which resolves which of those two hexes near the 3 have which numbers. Click through for each step.

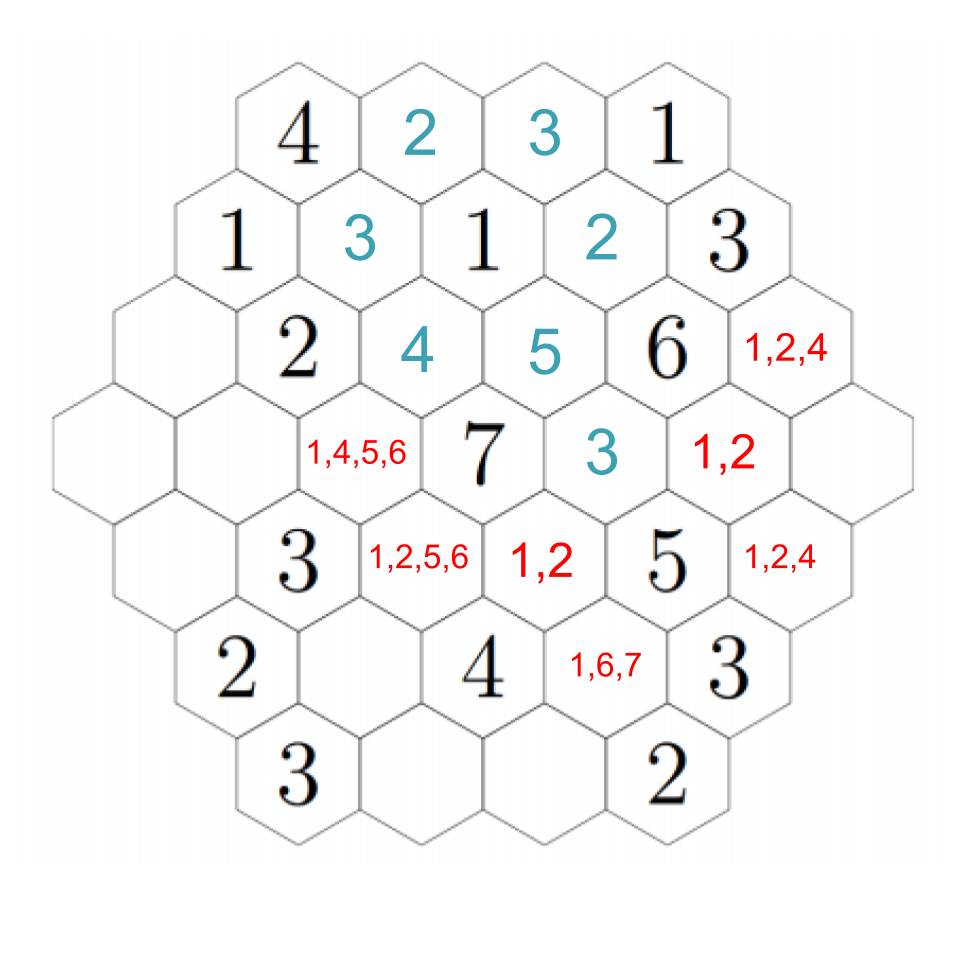

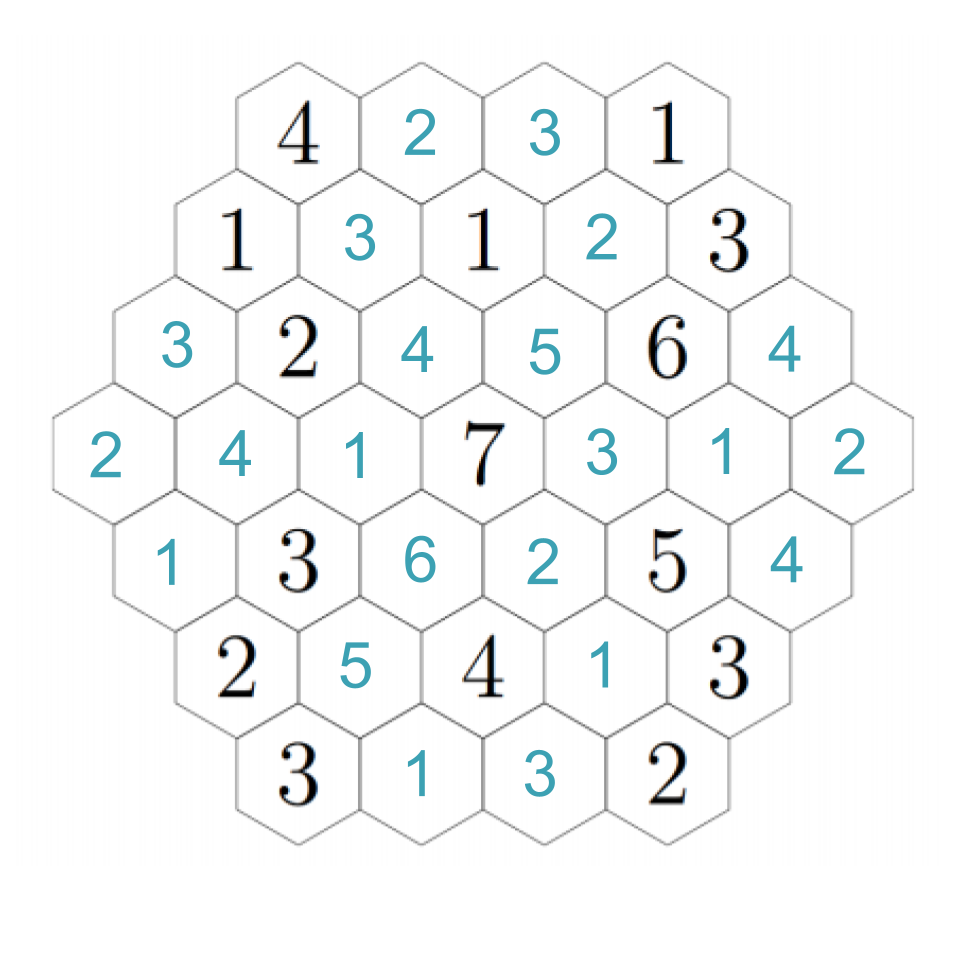

Now we can fill in several basically on autopilot. The 4 we just put in still needs an adjacent 2, so we fill it into the rightmost hex, which puts a 4 just below it, and the 3 in the lower-right still needs a 1, so we fill it into the only empty hex.

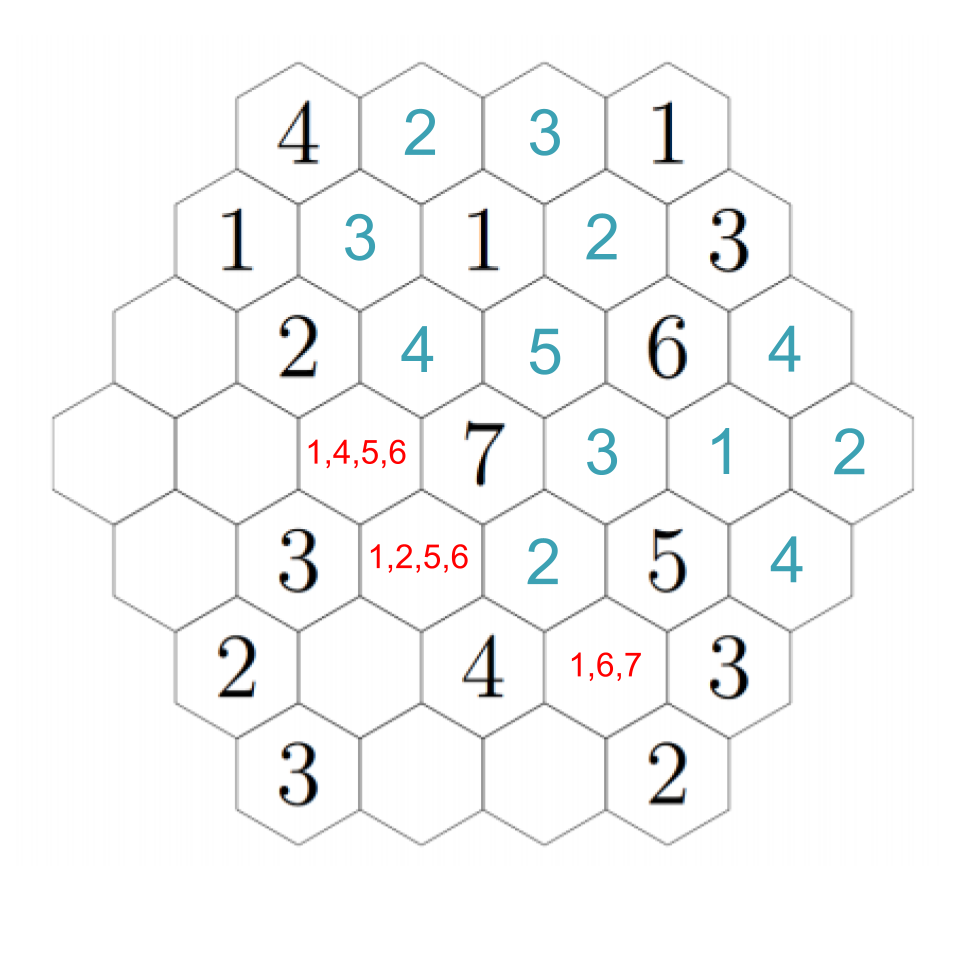

The hex just underneath the 1 must be a 3, because the remaining hex to its left cannot be a 3 so it just has 1 and 2 adjacent. Click through to see each step.

There's one other deduction we can make now. Look at the leftmost hex. None of the hexes next to it can be 2's because they're all next to 2's! That means it must be a 1 or a 2 itself. We'll figure out which in just a moment.

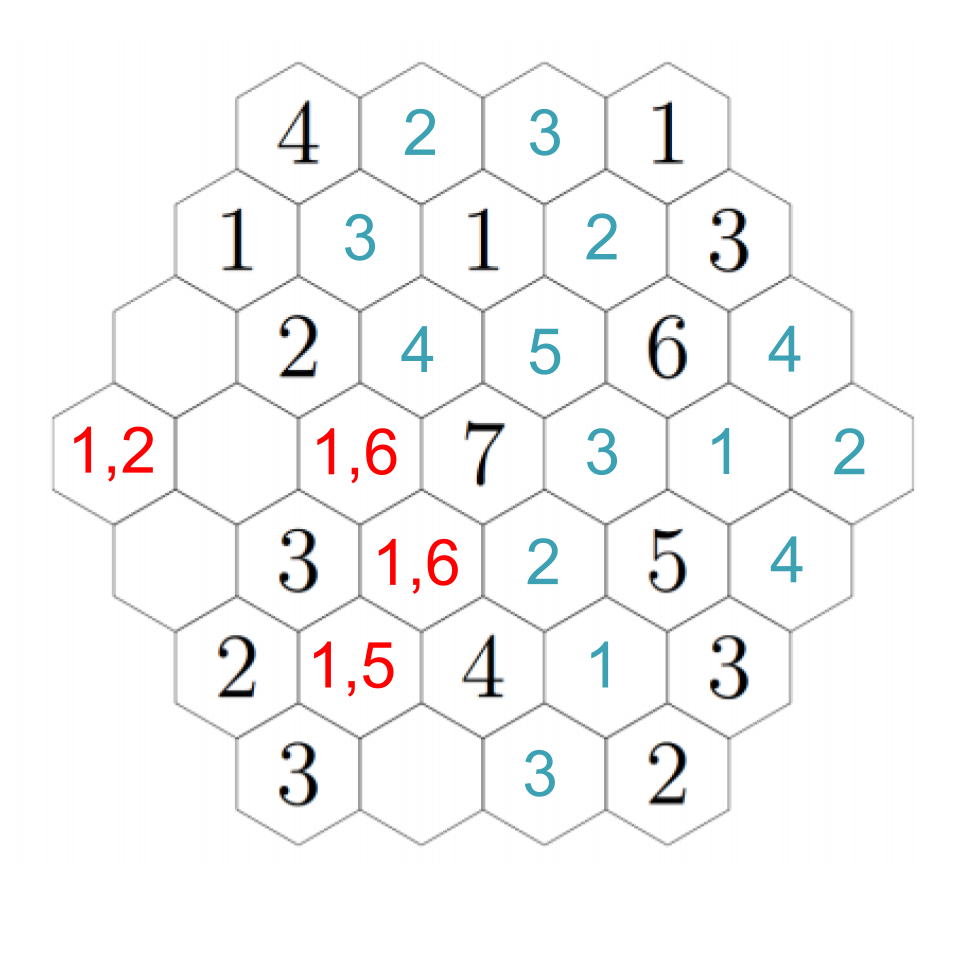

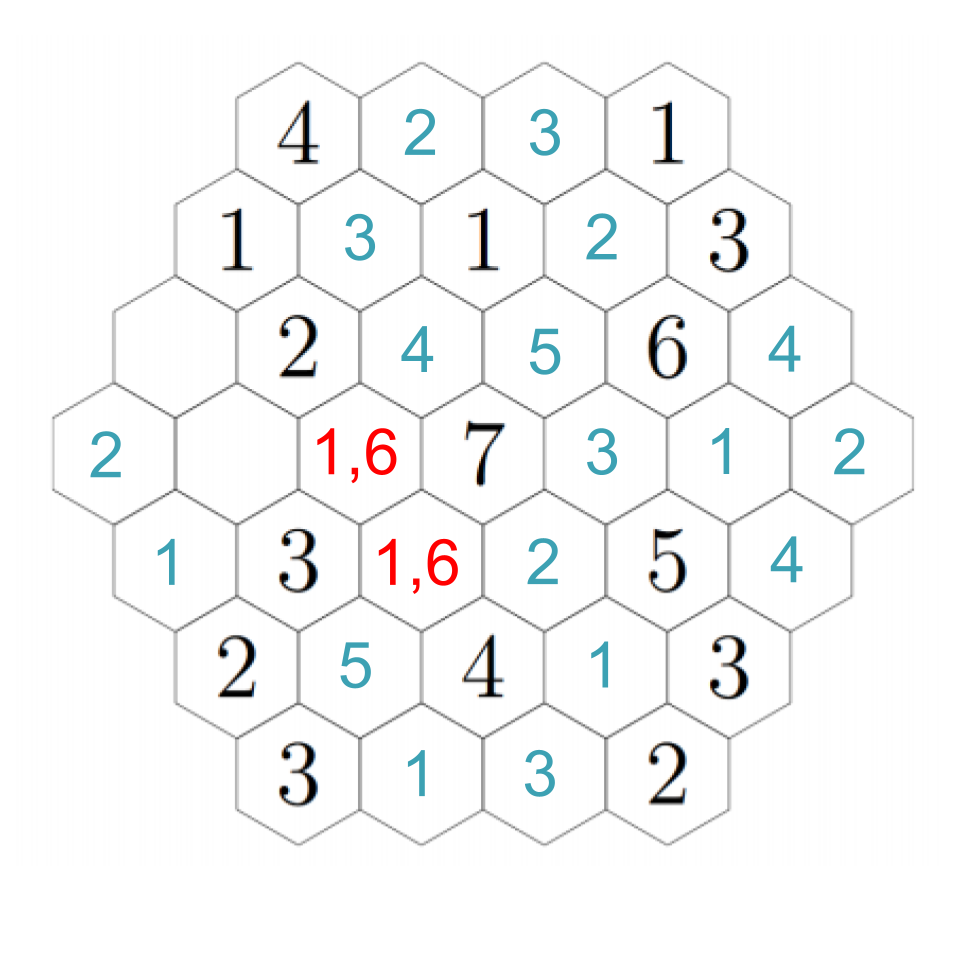

To resolve our remaining questions, look again at the 7. We still need a 1 and a 6, and in particular the hex down-left of the 7 must be a 1 or a 6. Down-left from that, we see another empty hex that can only be a 1 or a 5 --- except it can't actually be a 1. If we choose a 1 down-left from the 7, then this adjacent hex can't be a 1; if we choose a 6 down-left from the 7, this adjacent hex needs to be a 5 to make the 6. In any case, we put a 5 there. Then down-right from there we have a 1. The 2 to its left must be next to a 1, so that fills in a 1 in the remaining adjacent hex, which fills in a 2 in the left-most hex (which we already figured out must be a 1 or a 2, but now it's next to a 1). Click through to see the progress through these steps.

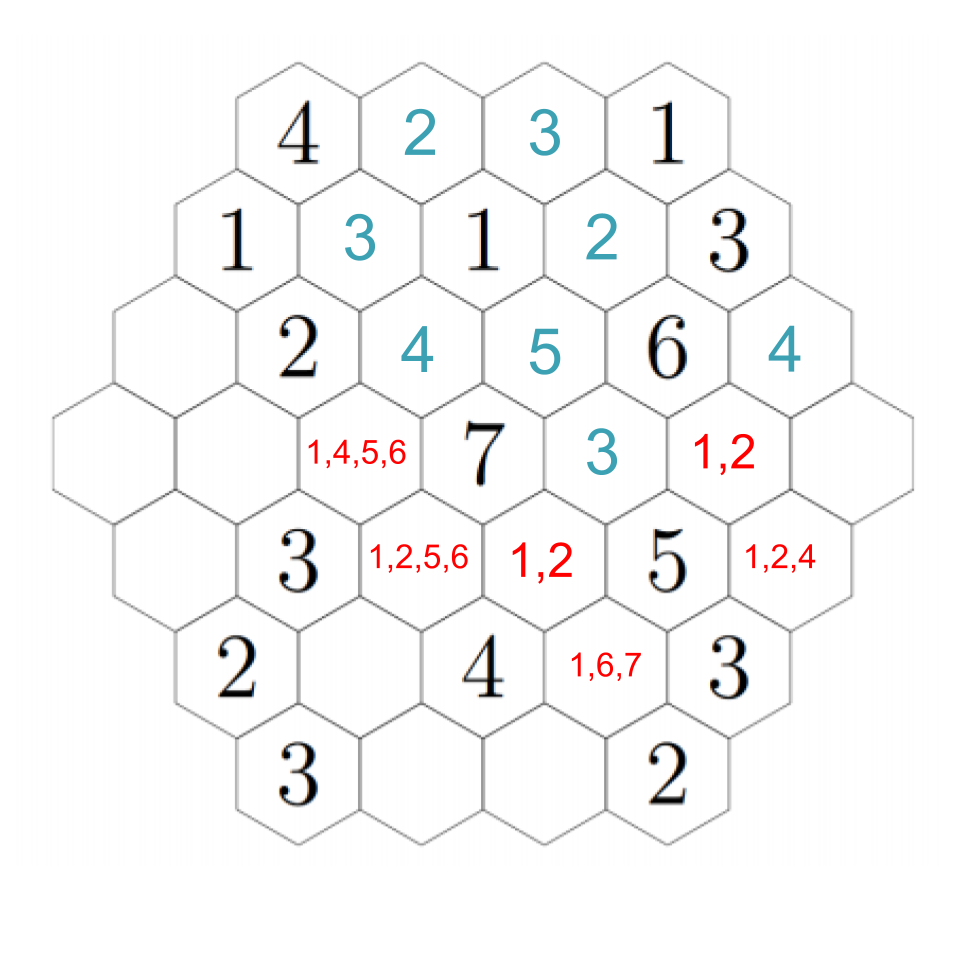

Up-right from the 2, the hex must be a 3 (because it cannot be next to a 3). Down-right from that, we must have a 4 (the empty hex is either a 1 or a 6). That confirms a 1 to the right, and a 6 down-right from that, completing the image. Click through these steps below to see the finished image!

BEAM Announces New National Program

BEAM National plans to reach thousands of students from low-income and historically marginalized communities nationwide.

BEAM Announces New Initiative in Collaboration with Art of Problem Solving to Increase Diversity in STEM Fields

BEAM National plans to reach thousands of students from low-income and historically marginalized communities nationwide.

Bridge to Enter Advanced Mathematics (BEAM) is excited to announce a new initiative in collaboration with The Art of Problem Solving to support students from low-income and historically marginalized communities nationwide in pursuing advanced mathematics.

BEAM National will provide access to advanced mathematics learning for students from second grade through college graduation, and in particular will provide continuous mentoring and advising from middle school through college. Our goal is nothing less than to change the landscape of achievement by both reaching students from a young age and providing access to the most marginalized students no matter where they are.

In BEAM National's Entry Points program, thousands of students will receive free access to the highly-regarded Beast Academy Online program in elementary school, as well as guided support from teachers, community organizations, and families; BEAM will provide training and support for their work with the students. Students who do well will receive free enrollment to online Art of Problem Solving courses in 6th and 7th grades, and can then continue to a national, residential summer program in the summer after 7th grade --- BEAM's Summer Away program, which will introduce them to beautiful and challenging topics in math.

Students who attend Summer Away will be a part of our Pathway Program from 8th grade-college graduation, which will include individual mentoring and advising, online classes, and a continuous community of all their friends from the summer. While the community will be online for most of the year, each year students from all years of the program will come together for a conference/reunion to reconnect and share their learnings, with a focus on older students mentoring their younger peers.

See below for answers to frequently asked questions. Those who are interested can get involved in a number of ways:

Apply for our new Executive Director of National Programs role, or share the role with your network.

If you are connected to a school, district, university, or community organization and want to make the program available to your students, sign up here to receive updates.

Donate to BEAM to support our work, including BEAM National.

Frequently Asked Questions

When will the program launch?

Academic year 2020-2021 is a learning year for us, during which BEAM staff will work closely with small groups of students to understand the most effective support for us to offer with Beast Academy. During academic year 2021-2022, we expect to pilot a school-led program (with professional development provided by BEAM) for around 500 fifth graders. The program will continue to scale based on initial outcomes, reaching students in both younger and older grades.

What support will BEAM provide to schools or others implementing the program with their students?

While we plan to iterate on the design, we expect to offer professional development, recommended activities to run with students, and easy access to student progress on the Beast Academy platform. For those near to some of our staff, we will also offer a monthly classroom visit to engage the students with fun activities and connect them to the broader BEAM community.

What commitment is required from partners?

Partners will commit to providing students with needed technology, giving them dedicated time to work on the platform, and providing support to students. While we recommend forming a separate class for students using Beast Academy, it is also possible for students to work independently with period check-ins from a teacher.

What support will BEAM provide directly to students?

In addition to Beast Academy, students will have access to videos from BEAM that will feature interviews with STEM professionals from diverse backgrounds, engaging demonstrations of mathematics, and special problems.

What support will BEAM provide to families?

We expect to provide families of participating students with monthly games and activities that family members can do together with the students. Parents/guardians will also be able to get reports on student progress.

What students are eligible? How much will the program cost?

Students must meet BEAM's criteria for being low-income and low-access (based on family income and the community/resources of the school they attend). The program will be free to all eligible students. Schools will be eligible to participate if the overall population is predominantly within BEAM's target audience.

What if my student/school is not eligible?

Individual students can sign up directly for Beast Academy. Schools can similarly acquire the curriculum for their use.

What will the mentoring look like during the Pathway Program?

Once students complete BEAM Summer Away, they will communicate regularly with a BEAM advisor to help them navigate high school, attend other summer programs, apply to college, and more.

How many students will ultimately be served by BEAM National?

While there is a lot we're still figuring out, when the program reaches scale we hope to be reaching tens of thousands of students per year.

What will happen with BEAM's local programs?

BEAM remains fully committed to our programs in both Los Angeles and New York City, and in fact we're looking at expanding those programs or opening in new cities. BEAM National affords us a new way to reach more students, and to ensure that geography isn't a barrier to students' access to advanced math. We expect there to be a robust exchange between the programs: local programs can learn from BEAM National's work with elementary-aged students, while BEAM National will learn from our mentoring program in high school and college. Our local programs will always be able to reach those students in the greatest need with our direct on-the-ground work, and if anything, our commitment to that work will only get stronger.

BEAM Summer Programs Go Virtual

BEAM faculty members are one of the keys to the success of BEAM programs and, quite simply, they are our heroes. In 2020, as we ran summer programs online for the first time, we asked even more than usual from our faculty―and that's saying a lot. Read about their experiences teaching online at BEAM summer programs.

BEAM faculty members are one of the keys to the success of BEAM summer programs and, quite simply, they are our heroes. This summer we asked even more than usual from our faculty―and that's saying a lot. In less than ideal circumstances, they shone.

It wasn't easy. Faculty dedicated untold hours not only to redesigning their own classes, but also to helping us create an online summer program from scratch. We're still thinking a lot about what we learned in our first summer online. Here's what three of our faculty members told us about their experiences.

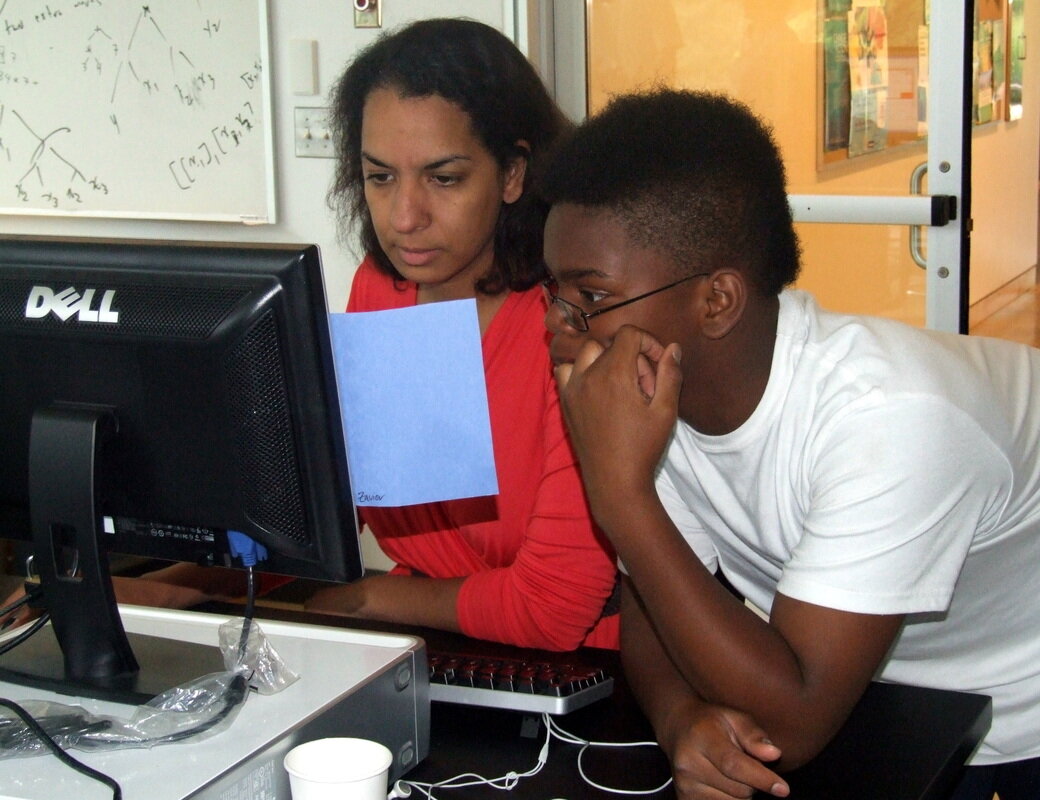

Susan Donovan, a faculty member at BEAM Discovery New York City, taught Circuits and Programming and reflected on how teaching online compared to teaching in person.

Students learned the definition of a circuit and the basics of reading schematics, polar vs. non-polar components and how to use a breadboard in Susan’s class. They all shared photos of their first working circuit.

I've taught circuits and programming with BEAM students in person twice so I know how exciting and rewarding the course can be, but I was very nervous about moving it online. But we mailed out kits to all of the students, and I frantically created webpages to help them document their projects and somehow it worked out!

The greatest challenge was not being able to really see what students were doing. Normally, I'd walk around the room and give hints and corrections as students interpreted circuit diagrams or edited code. It's possible to do something similar to this with screen sharing and video, but it's just not as easy.

One upside though, I think this limitation helped some students to become more independent. One of the nice things about teaching electronics is it's clear to a student when their work is wrong. The light simply won't turn on. It's a process that teaches patience and persistence. I had one student who wired a project five times before all of the errors were removed, and the whole class celebrated her victory!

Taylor Corcoran taught Games and Strategies at BEAM Discovery Los Angeles. In this class, students learn how to analyze games to find "winning strategies," that is, strategies that allow them to win the game no matter what the other players do.

My main goal for this class was to get students excited about learning math, and to show them that math plays a role in so many different parts of our lives. Another goal I had was to strengthen students' logical reasoning skills and to push them towards rigorous mathematical thinking and proofs.

Teaching online was definitely a challenge! My main concern about teaching a games class online was how to have students play games with each other virtually. In person, many of the games we played relied on manipulatives such as bingo chips and notecards, and I wasn't sure how to transfer this online. Luckily several other staff members had experience teaching games online and had great recommendations, including using Google Slides and Classkick. I ultimately decided to use Classkick, which allowed students to move manipulatives around the screen, to draw freely, and to type up their answers to questions.

Brian, Jasmin, Camila, Cristina, and Arely play Dots and Boxes with their TA, Cyril.

For me, a huge challenge was getting used to all the different moving parts of online instruction. Not only do you have to deliver content, but you have to check students' facial expressions to see if they are confused, read the chat, listen to students as they turn on their mics (as well as mute people with noisy backgrounds!), and place students into breakout groups! I'm also not the most tech-savvy person, so it was challenging to master all the new technology.

As for the advantages, I did really enjoy getting to teach in my pajamas, and the commute was unbeatable. But besides that, yes, there were several aspects of teaching online that I really grew to appreciate. I think the chat feature of online learning was a game changer for quieter students who, even in person, may not have been willing to raise their hand and share their thoughts. Having the chat lowered students' inhibitions around participating in class and allowed them to formalize their ideas.

There were also activities that ended up working much better online than they had last year when I taught the class in person. For example, on the last day of class, we explored a website that teaches students about the Prisoner's Dilemma, a famous game in game theory. In person, we did the activity as a class, and I projected the website on the board. This year, though, I turned the activity into a competition between breakout groups, and students got really into it and were determined to beat the other teams.

During the five weeks of the program, students found winning strategies (and articulated why they were winning strategies) for several games, including Nim and Chomp. They also learned about the difference between being fair (splitting items equally between people) and being rational (making decisions that are in your best interest). We wrapped up the class with learning about strategies in the Prisoner's Dilemma.

Taylor’s class posed for a photo on their last day.

Cory Colbert taught Irrational Numbers & An Introduction to Proof (Irrational Numbers) in the first two weeks and Analytic Number Theory (ANT) in the last two weeks at BEAM Summer Away Los Angeles.

For Irrational Numbers, my goal was to have students prove that the square root of two is not rational. For ANT, my original goal was to talk about Dirichlet's Theorem on Arithmetic Progressions. I did that during Summer Away in 2019, but this summer, we instead proved that there are infinitely many prime numbers.

One of the major challenges of teaching online is not being there in person and not being able to scan the class as a whole and see who is following and who needs more attention. The dynamic is just different online because it’s more distant.

Daisy used ideas from Cory’s Irrational Numbers class to prove that the square root of 5 is irrational.

I was mostly looking for a way to have them work in groups, and Zoom breakout rooms made that happen. Breakout rooms cut out all distractions, which is great. I didn't have to worry about one group being distracted by another group, and it was a lot easier to focus any particular group on a strategy. Also, it's easy to record classes if that's your thing.

From my point of view, the students developed a higher appreciation for rigorous proof and reasoning, which is what I go for. One student wrote, “We got to learn how to prove and we learned the Euler of a number and how to find it. We also learned the definition of many symbols and variables, how to use them and how to apply them in the real world or when proving something.”

... And Now for Some Math

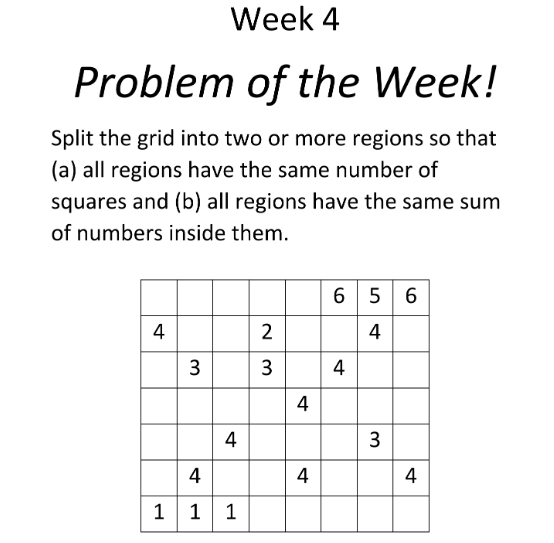

Try your hand at a Problem of the Week from BEAM Discovery (our summer program for rising 7th graders)! The Problem of the Week gives students a chance to explore interesting math outside of their classes, either on their own or in collaboration with others.

Try your hand at a Problem of the Week from BEAM Discovery (our summer program for rising 7th graders)! The Problem of the Week gives students a chance to explore interesting math outside of their classes, either on their own or in collaboration with others. It also provides an opportunity to build relationships with site leadership (who usually grade the problems), and a chance for staff to celebrate persistence in problem solving. This summer, students who solved a Problem of the Week received a special badge. See if you can solve Week 4’s Problem of the Week!

Solution:

One of the BEAM Discovery students who solved this problem was Jayden. You can see his submission at the end of this post!

There are 56 squares in the grid, which has to also be equal to the number of regions times the number of squares in each region. Meanwhile, the sum of the numbers is 63, which has to also be equal to the number of regions times the sum in each region. This is where we can combine two facts to make the problem simpler: the number of regions must divide both 56 and 63! Since the only common divisors are 1 and 7 (and one region doesn't solve the problem), there must be 7 regions. Dividing, we see that each region has 56/7=8 squares, and the sum in each region is 63/7=9.

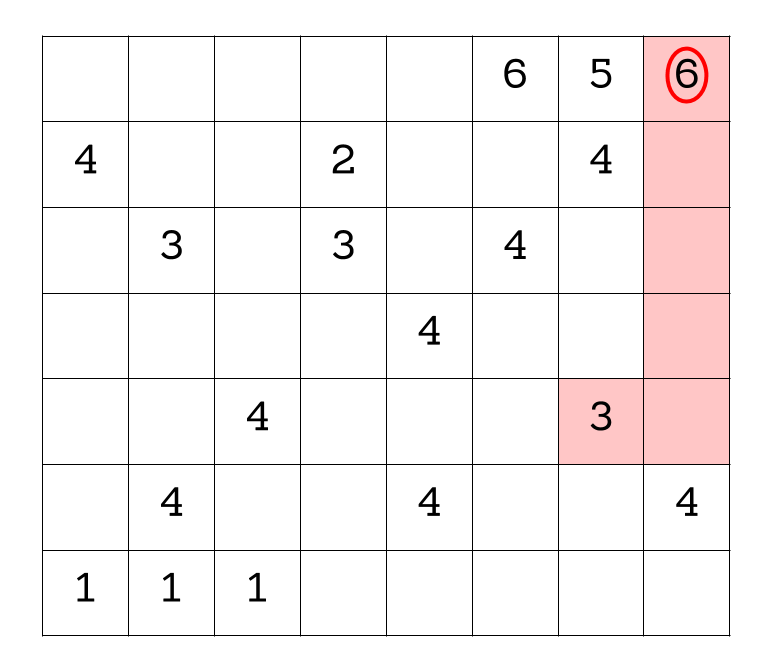

Now that we are satisfied that the only possible solution will have 7 regions with 8 squares in each region and each region should sum to 9, we still have the very tricky task of figuring out if we can actually come up with such a configuration. This seems like a pretty daunting task. One way to make it a little easier is to start with the squares containing large numbers (like 5 or 6) since there might be more limited options for the regions that contain them.

It also helps to lay out a couple of “rules” that help guide how we can build regions.

A number can’t be paired with a number that is “too far away.” Too far away means that it would take too many blocks to include it in the part of the region that is already determined, since each region can only be 8 blocks in total. For example, the 6 in the top right can’t be in the same region as the 1 in the bottom left, because it would take too many blocks to connect them.

Each region must contain exactly one odd number. Why? Because each region has to sum to 9, which is an odd number; therefore, it must contain at least 1 odd number. But there are exactly 7 odd numbers in total on the grid, so none of the 7 regions can contain more than one.

Just a note: To save time on the explanation, we're going to make a few simplifying guesses, but it is possible to solve the entire puzzle without having to make any guesses about how things come out!

First let’s think about the two 6’s, because those seem like they might be the easiest. Because the 6’s are the biggest numbers in the grid, and they can’t be paired with any 4’s or 5’s, this helps immediately narrow down our options. They also can’t be paired with any of the 1’s, according to rule 1, since the 1’s are too far away.

Starting with the 6 in the upper righthand corner, there is only one 3 available to be included in this region, as all the other 3’s are too far away/we would need to include another number in the region which would make it to have too high of a sum.

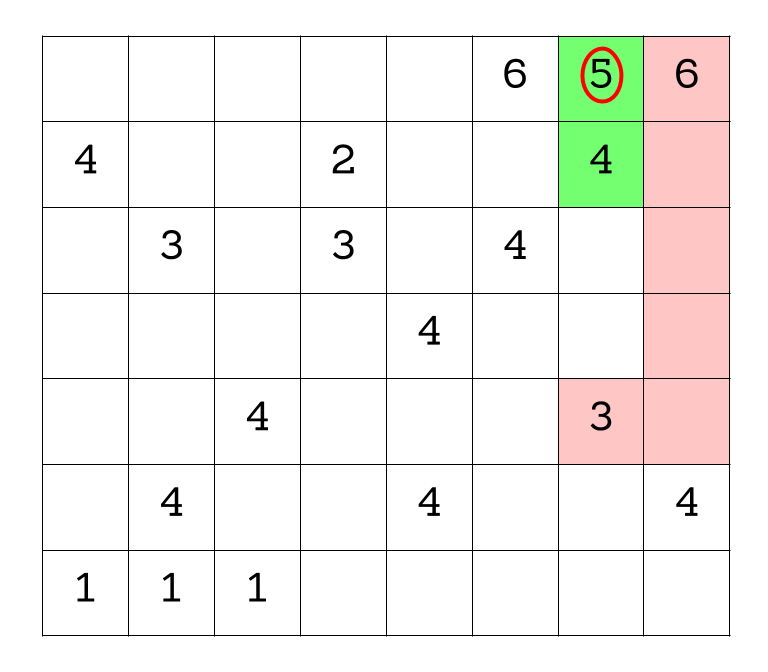

Now turning to the only 5 in the grid we know it must include the 4 immediately below it because that is the only direction we can expand this region without including a 6 and bumping our sum up to 11, which is too high.

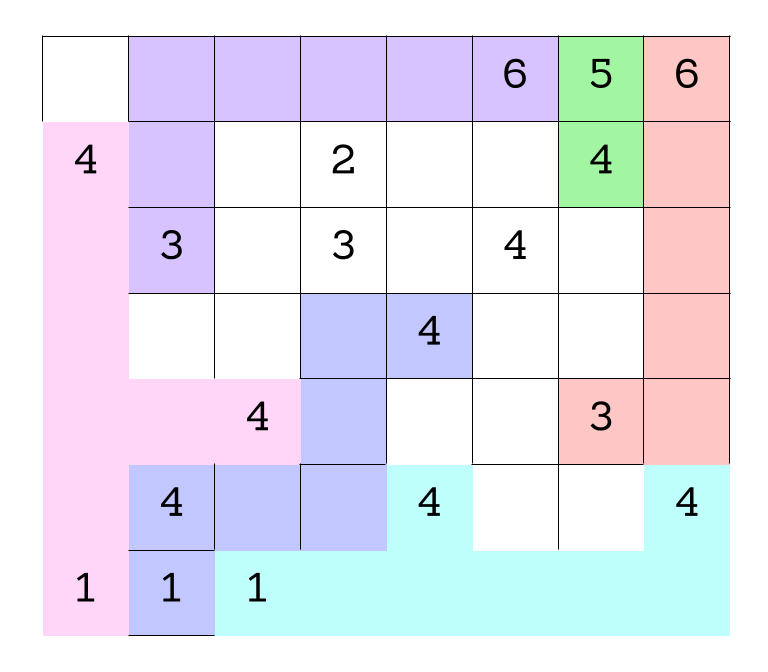

Next I would like to tackle the 6 that is remaining but it is hard to figure out which 3 belongs in the same region as it since neither is too far away. So, let’s look at the 1’s. Because they are odd, each one has to be in its own region. And because they are adjacent, we have fewer directions we can go.

Starting with the 1 in the bottom lefthand corner, we know it has to include the two 4’s (indicated in the figure below). All the other even numbers are either too far away (shown in red) or if we included them in the new purple region we would cut off the other 1’s so that they would need to share a region, which we can’t do (we have highlighted those numbers in green). So, none of those numbers can be included in this region leaving only 2 available 4’s to be included in pink.

Moving on to the next 1 (circled in red) we see again most of the even numbers are too far away to be included in this blue region (in red). There is just one 4 that is close enough to work, but if we include it in blue the 1 that is leftover will be cut off from all but a single 4, which would not be a workable region. So, the green 4 can’t be included either, leaving us with the blue region shown below.

At this point you might be thinking,Wait! The green region has only two tiles, the pink region has 8, the salmon-colored region only has 6. Aren’t they all supposed to have 8 tiles in a region?

Well, that’s right, each region does need to have eight tiles in our final solution. But it is really hard to see how blank tiles should be assigned to make everything work out, so we will start by just figuring out which numbers should share a region, and then see if we can divvy up the blank tiles from there. That’s why our regions will each add up to 9 to start with, but they may not have 8 tiles in them just yet.

Now we just have one 1 left and two of the remaining even numbers (highlighted in red) are too far away. If we included the other 4 (highlighted in green) then we would end up cutting off the 4 in the bottom right corner. With just two of the 4’s left, we know that they should be included in the turquoise region below.

Now we can finally circle back to the remaining 6, and try to figure out which 3 it should be paired with. Now if we pair it with the right-most 3 (in green) we will cut off the remaining 4 from all the other numbers, which isn’t allowed. That leaves the 3 on the left, which we will include in the purple region.

The last numbers standing 2,3, and 4 of course must share a region. But now that we know which numbers share a region, let’s move on to expanding regions to have exactly 8 squares.

Two of the regions are already exactly 8 squares (pink and turquoise).

Now the only region the top left square can be included in is the purple region, which brings the purple region to a full 8 squares.

Now that the pink and purple regions are more settled we can tackle the last three numbers. We know they have to share a region (grey). The square outlined in red also has to be grey because if it was part of the blue region, then the blank square to the left of it would be cut off and couldn’t be added to any of the regions next to it.

With the four grey squares above filled in, we can complete the grey area, since all the blank squares to the left of the grey area have to be filled in grey and the 4 in grey has to be included in the grey region.

The green region must expand into the blank squares to the right and then down to keep it a single region of exactly 8 squares.

And with that we can complete the final region (salmon colored). Whew! What a process!?!

A few more questions

Now we can verify that this solution is indeed a solution, just by checking that each region does sum to 9 and each region does have exactly 8 squares. But another question you may be asking yourself, and what a mathematician might ask themselves about a solution like this, would be:

Is this the only solution (i.e. is it unique)? If it is the only solution, how could you show that it is the only one?

If you enjoyed solving this problem, you can tackle the additional questions above for some bonus fun. :)

Jayden’s Solution, BEAM Discovery 2020

This problem comes from USAMTS, a national math contest.

College Decision Day: Congratulations High School Seniors!

During times of change and stress, it takes courage to make big decisions. Last spring, our high school seniors stepped up to the challenge as they navigated college decisions this year. We're proud to announce the schools our students will be attending.

During times of change and stress, it takes courage to make big decisions. Our high school seniors are stepping up to the challenge as they navigate college decisions this year. We are so proud of all the BEAM students who are starting college in the fall!

We're pleased to announce the schools that the following students will be attending:

Images from left to right display: Jennora (Brown), Tiffani (Georgetown), Bob (Syracuse), Nhyira (New York University), Crystal (Wesleyan), Deoles (Skidmore), Adrian (SUNY Plattsburgh), Rebecca (Tufts), Karoline (Vassar), Joel (Babson), and Yohely (Wesleyan).

In addition to the 11 students pictured above, we want to congratulate all our graduating seniors. Here's a list of BEAM students currently ready to announce their college decisions:

Aamari: SUNY Oneonta

Adrian: SUNY College at Plattsburgh

Alberto: University of Wisconsin-Madison

Amerie: CUNY Lehman College

Boburmirzo: Syracuse University

Brianna: Wheaton College

Chaille: College of Mount Saint Vincent

Chukwuka: Rochester Institute of Technology

Crystal: Wesleyan University

Deoles: Skidmore College

Eliana: SUNY Polytechnic Institute

Esteeven: Columbia University

Isabella : Vanderbilt University

Jennora: Brown University

Joel: Babson College

Johnathan: Wheaton College

Karoline : Vassar College

Kaylee: Syracuse University

Malachi: SUNY at Albany

Mariam: Barnard College

Michael: CUNY Hunter College

Nhyira: New York University

Olivia: CUNY Hunter College

Rebecca: Tufts University

Sam: SUNY College at Geneseo

Sonobia: Marymount Manhattan College

Tiffani: Georgetown University

Veronica: CUNY John Jay College of Criminal Justice

Yohely: Wesleyan University

Zoë: Amherst College

BEAM students were also awarded many scholarships and other forms of financial aid:

Alberto (University of Wisconsin-Madison), Isabella (Vanderbilt), and Jonathan (Wheaton) were selected to be part of the Posse Scholars Program, which provides students with a full-ride scholarship, as well as connections to other students in their area who attend the same college they plan to attend.

Esteeven (Columbia) and Yohely (Wesleyan) were selected to be part of the QuestBridge National College Match Program, which provides a full-ride scholarship through college to students who are accepted at one of the program's partnering schools.

Jennora (Brown) earned a Gates Scholarship, which provides funding for the full cost of attendance that is not already covered by other financial aid and the expected family contribution.

And numerous other students were offered amazing financial aid packages by the colleges they will attend. The scholarships provided by Amherst, Bowdoin, Brown, Columbia, Harvard, University of Chicago, and Vanderbilt are particularly generous, as these schools meet 100% of demonstrated need (without loans). Some scholarships are even generous enough to cover additional expenses that may come up, such as flights to and from home at the start and end of each semester.

Our seniors did an incredible amount of work to get through high school. Congratulations to you all! 11th graders: now it's your turn and BEAM is here for you.

For those following along at home, here is a list of the colleges to which BEAM students were admitted this year:

Adelphi University

Alfred University

Adelphi University

Alfred University

Amherst College

Babson College

Bard College

Barnard College

Bowdoin College

Brown University

Cedar Crest College

College of Mount Saint

Vincent

Columbia University

Cornell University

CUNY Bernard M Baruch

College

CUNY Borough of

Manhattan Community

College

CUNY Bronx Community

College

CUNY Brooklyn College

CUNY City College

CUNY City Tech

CUNY Hostos Community

College

CUNY Hunter College

CUNY John Jay College of

Criminal Justice

CUNY LaGuardia

Community College

CUNY Lehman College

CUNY Medgar Evers College

CUNY Queens College

CUNY York College

Drew University

Fordham University

Franklin & Marshall

College

Georgetown University

Georgia State University

Goucher College

Grinnell College

Harvard University

Hawaii Pacific University

Hofstra University

Howard University

Ithaca College

Juniata College

Knox College

Lehigh University

Long Island University

Macalester College

Manhattan College

Manhattanville College

Marymount Manhattan

College

Middlebury College

Monroe College

Morgan State University

New York Institute of

Technology

Northeastern University

Notre Dame de Namur

University

New York University

PACE University

Pennsylvania State University-

Altoona

Rensselaer Polytechnic

Institute

Rochester Institute of

Technology

Siena College

Skidmore College

Spelman College

St John's University-New

York

Stockton University

Stonehill College

SUNY at Albany

SUNY at Binghamton

SUNY at New Paltz

SUNY at Purchase College

SUNY Buffalo State

SUNY College at Geneseo

SUNY College at Oswego

SUNY College at Plattsburgh

SUNY Cortland

SUNY Oneonta

SUNY Polytechnic Institute

SUNY Stony Brook

University

SUNY University at Buffalo

Syracuse University

The College of Saint Rose

Tufts University

University of Chicago

University of Connecticut

University of Minnesota-Twin

Cities

University of Oregon

University of Pennsylvania

University of Puerto Rico -

Mayagüez

University of Rochester

University of Virginia-Main

Campus

University of Wisconsin-

Madison

Vanderbilt University

Vassar College

Washington University in St

Louis

Wesleyan University

Wheaton College

Williams College

Worcester Polytechnic

Institute

York College

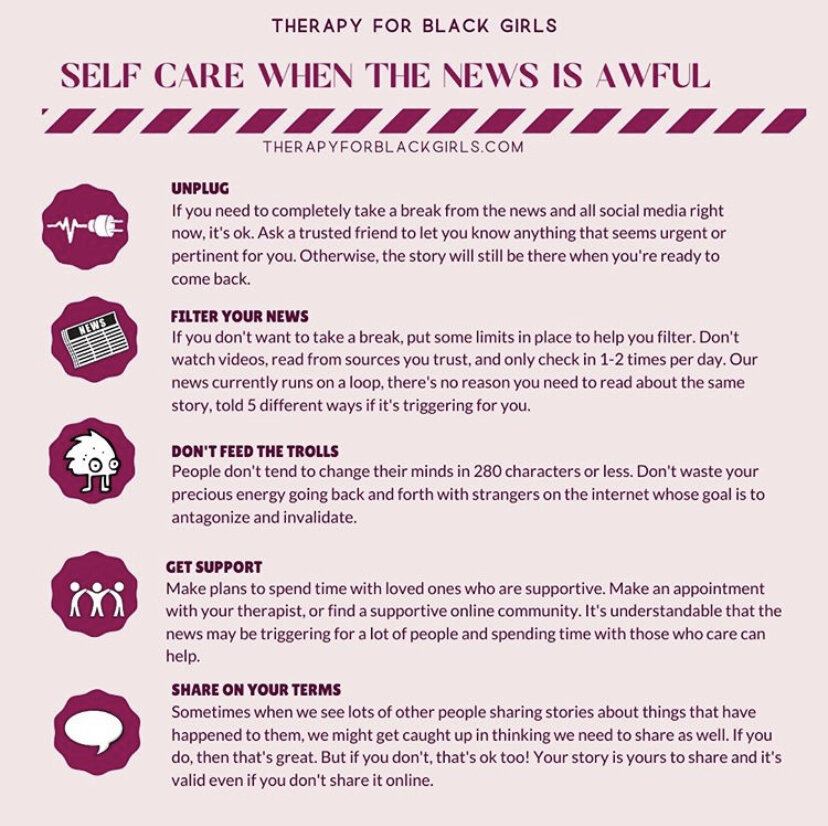

BEAM's Mental Health Resource Round-up

For May Mental Health Awareness Month, BEAM staff and students hopped on our social media to share our favorite ways to take care of our mental health during this challenging time!

Quarantine with BEAM

For May Mental Health Awareness Month, BEAM staff and students hopped on our social media to share our favorite ways to take care of our mental health during this challenging time!

Sylvia - BEAM Staff - described what mental health is and why it is important.

Alyssa - BEAM Staff - shared how storytelling helped her cope with trauma.

Isabella - BEAM Staff - guided us through some breathing exercises.

Gianni - BEAM Summer Staff - talked about the connection between physical and mental health.

Crisleidy - BEAM Student - helped us focus on self-care with a make-up tutorial.

Esteeven - BEAM Student - shared how he and some of his peers have found a creative way to help young people learn more about mental health.

Throughout the month we also shared favorite resources related to mental health on topics including grief, self-care, and coping. You can explore those resources below.

Grief and COVID-19

Living through a global pandemic can be traumatic as we grieve the loss of freedom, independence, or even a loved one. We're collectively going through a traumatic event. But while we may be in this together, it certainly isn’t impacting us all equally.

COVID-19 and the grief it has brought with it have disproportionately affected Black and brown communities. It's important to hold space and recognize that the impacts of COVID on people of color in America are part of a larger picture of trauma.

Click through these images for information and resources for Black and Latinx communities.

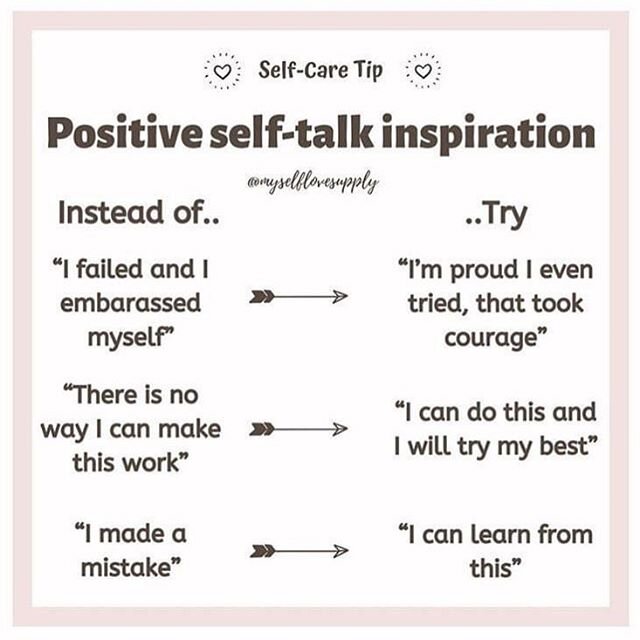

Self-Care

During these tough times it is especially important to take care of yourself. Self-care is a variety of activities, practices, or rituals we engage in on a regular basis to reduce stress and enhance our well-being. It's really important that when we are struggling or feeling stressed that we find daily routines and practices that bring us joy. Self-care can look like so many different things: it can be taking a walk during a stressful situation, doing deep breathing exercises, taking on a new hobby, connecting with a friend, or listening to music.

Click through these images for some self-care resources to help you do just that.

Ways to cope

May is over now, but mental health awareness doesn't end here. As racial violence, systemic injustice, and a pandemic continue to play out across our country, continuing to practice healthy and effective coping is more important than ever.

Click through these images for some additional coping resources.

Zavier's College Journey

Zavier is part of BEAM’s first cohort to graduate from college (in 2020); he graduated from UAlbany with a double major in computer science and art. He is also BEAM’s first alum to serve in a leadership role at our summer programs.

As families across the nation and around the world celebrate their graduating college seniors, BEAM couldn’t be more proud to celebrate our own cohort of graduating seniors for the very first time! We wanted to take this moment to highlight a BEAM student who has been with us from the very beginning. Zavier attended BEAM Summer Away in 2011, our very first summer program. Over the years he has come back to BEAM as a counselor multiple times, and last summer he became the first BEAM alumni to play a leadership role at a summer site, serving as the Director of Student Life.

He sat down with BEAM (virtually of course) to share some wisdom from his time at college.

What are you most proud of from your time at college?

Well, to start I am very proud that I was able to finish my studies with a major in both Computer Science and Art. When I first went to UAlbany I had gone to study Computer Science and was told that I'd probably end up switching to informatics because Comp Sci is a hard major. I was also told that I shouldn't major in Art because it was too easy and I wouldn't be able to find a real job. So when I started college I challenged myself to see if I could do both. From studying these two subjects I was able to better understand my interest and what my education meant to me. From studying Comp Sci I learned how to be more patient and proactive with my school work. With Art I learned how to organize my own thoughts and work with intent.

What was a favorite moment from your time with BEAM (so far)?

Although I've had many memorable moments with BEAM, one of my favorite moments is the hiking trip we went on last summer [2019] at BEAM Summer Away. It was nice because a lot of the campers bonded with the staff in unexpected ways. It was a pretty calm trip and I was glad that everyone else enjoyed it too.

Looking back at your college career, what surprises you most?

Looking back at my college career, the thing that surprised me the most was how much planning you actually need to do to really have a semester that works for you. When I started college I figured I'd be fine if I just went to my classes, but I learned that it takes more than just going to class to be successful. At first I had to get used to making time to study. Then I learned how to properly make my class schedules. After I understood what worked for me I was able to stress about classes less and organize my time better. I believe I was so surprised by these things because it was one of the responsibilities I didn't really think about with the new found freedom that I had.

Overall, my college experience was pretty different than what I expected.

There were many times that things did not go as I planned, but those events really helped me mature and change my perspective on my work and my interest. I also learned the importance of having people around you that share the same interests. Sometimes opinions may differ, however I saw how differences in ideas may lead to better ones. From learning how to work around roadblocks and work with others, I was able to enjoy my experience. I was able to let go of expectations on how I wanted things to go and started using what I had to reach my goals.

Thank you to Zavier for his wise and timely words, and congratulations again to all of our graduating college seniors!

...And Now for Some Math

Here’s a math game you can play while keeping up social distancing. Find someone to play with and read on.

The game:

You are given $20, and you must guess a whole number between 1 and 700. For each incorrect guess you make, you must pay $1, and then you are told if you were over or under the correct number. If you guess the number, you get to keep the money you have left.

Challenge 1: Can you guarantee a profit on this game? What's the greatest profit you can guarantee even if you are very unlucky on your guesses?

Let’s play a game!

Here’s a math game you can play while keeping up social distancing. Find someone to play with and read on.

The game:

You are given $20, and you must guess a whole number between 1 and 700. For each incorrect guess you make, you must pay $1, and then you are told if you were over or under the correct number. If you guess the number, you get to keep the money you have left.

Challenge 1: Can you guarantee a profit on this game? What's the greatest profit you can guarantee even if you are very unlucky on your guesses?

A Twist:

You are playing the same game as before, except now it has a twist: each time you guess, you pay $1 if you were under the correct number, but you pay $2 if you were over the correct number!

Challenge 2: Now can you guarantee a profit on the game? What's the greatest profit you can guarantee even if you are very unlucky?

Before diving into the solutions, we hope you’ll take some time to work on the answers. Spoiler alert: We’re going to show you the answers up front before our in-depth solutions, so you can try to match or even beat our answers.

Answer to challenge 1: Yes. We can guarantee a profit of at least $11.

Answer to challenge 2: Yes. We can guarantee a profit of at least $7.

Solution to Challenge 1:

If we randomly guessed 20 different (whole) numbers between 1 and 700, we would have less than a 3% chance of correctly predicting (since 20/700 = 0.0285…). Thus, we’re going to have to be a bit creative and use that we’re told how our guesses compare to the correct numbers.

Since I’m not sure about how to solve this problem, let’s consider a simpler problem and suppose instead the correct number lies between 1 and 30. We still can’t guess each possible number, so let’s think about a few possibilities for the first guess:

Table 1: Outcomes of possible first guesses if correct number between 1 and 30

Ah… we see that each incorrect guess leads us to a smaller collection of possibilities: the “Under” numbers or the “Over” numbers. So, to guess the correct number, we either need to get lucky with one of our guesses, or reduce down to 1 possibility then guess that 1 number. Since we might be very unlucky, let’s try to figure out a way to get down to just 1 possibility.

Back to the original problem, what’s the best first guess to reduce the number of possibilities? Well, if we choose a middle number, like 350, then we would cut the number of possibilities in half (or correctly guess). This means that the correct number is either between 1 and 349 (for “over), or it’s between 351 and 700 (for “under”).

Let’s repeat this. If the number is between 1 and 349, we can choose the middle number 175, which will leave us with 174 possibilities (if 175 is incorrect). On the other hand, if the number is between 351 and 700, we can choose a middle number 525, which will leave us with 174 or 175 possibilities (if 525 is incorrect).

So, it will cost at most $9 to guess the correct number between 1 and 700, which means we are guaranteed a profit of at least $11.

In general, suppose we were asked to guess a number between 1 and n. Then, the max cost to predict the right number is one less than the number of times we can halve n before arriving at a result strictly less than 1, which is:

log2(n), rounded down to the nearest whole number.

For example, log2(700) = 9.45…, which rounds down to $9 as we found above. Ah, I knew there was a reason we used to slog with logs!

Small tangent, if someone ever comes up to you at a party asking you to play this game with $20 and guessing a number between 1 and a million, you’re guaranteed to win at least $1 since

log2(1,000,000) = 19.93…,

which rounds down to 19!! (This is a really, really fun party game by the way.)

If you’d like to learn more about this search strategy and even use programming to code it up, you can look up “binary search algorithm”.

Solution to Challenge 2:

For the second challenge, we could try the same algorithm of halving the number of possibilities with each guess. If we do this, we can deduce that we’re guaranteed to earn a profit. Why? Well, each wrong guess costs at most $2. Since our solution to Challenge 1 required at most 9 wrong guesses, finding the right number here will cost at most $2 x 9 = $18. Hence, we will earn a profit of at least $2!

But that estimate seems… rough. Some guesses cost only $1. How can we use this fact to arrive at a better outcome?

Well, this problem seems… tough. So, let’s try a “bottom-up” approach of looking at some base cases, and hopefully find a pattern we can knead into a solution. Let’s try to solve the problem:

Starting with $x, what is the maximum whole number n(x) such that we can predict any number from 1 to n(x)?

Start with $0: We can’t afford to be wrong with any guess, so we can correctly predict only between 1 and 1, and n(0) = 1.

Start with $1: We will only be able to pay if our wrong guess is under, so n(1) = 2. We can predict 1 with our first guess, and then if we’re under, we can correctly guess 2.

Start with $2: Now things get more interesting because we can use our previous work. If our first guess is:

Under: We will have $1 remaining, from which we can predict correctly if there are at most n(1) = 2 possibilities remaining.

Over: We will have $0 remaining, from which we can win if there is at most n(0) = 1 possibility remaining.

This means that we should guess 2 with our first guess, and n(2) = 4.

Ah, we’re getting somewhere! Let’s try again.

Start with $3: If our first guess is:

Under: We will have $2 remaining, which we can predict from n(2) = 4 possibilities.

Over: We will have $1 remaining, which we can predict from n(1) = 2 possibilities.

This means that we should predict 3 = n(1) + 1 with our first guess, and n(3) = n(2) + n(1) + 1 = 7.

In general, suppose we start with $x, where x > 2. If our first guess is:

Under: We will have $(x-1) remaining, which we can correctly predict from n(x-1) possibilities.

Over: We will have $(x-2) remaining, which we can correctly predict from n(x-2) possibilities.

Hence, we should predict n(x-2) + 1 with our first guess, and

n(x) = n(x-1) + n(x-2) + 1.

Wow, this recurrence relation is like a modified Fibonacci sequence. Neato!

We can then use a table to solve our problem:

And there we have it! 700 is between 609 and 985, so it will cost at most $13 to correctly guess. This guarantees a profit of at least $7 no matter our unluckiness, a big improvement over the $2 profit we were guaranteed by repeated halving!

If you enjoyed this problem here are some additional problems to keep the fun going:

Additional question 1: What’s the highest profit that could be guaranteed if it cost $2 each time we were wrong and were asked to guess a number between 1 and 700? Are we guaranteed to earn a profit if it costs $1 each time we’re under and $3 each time we’re over?

Additional question 2: For Challenge 1, if we assume the machine randomly picks a number between 1 and 700, what is the average profit we expect to earn?

Additional question 3: Can you find a closed formula for nx in Challenge 2 using:

n(x) = n(x-1) + n(x-2) + 1, n(0)= 1, n(1) = 2?

... And Now for Some (Pirate) Math

Are you up for the 100 Problem Challenge?

These are optional (and very challenging) math questions that students at BEAM Discovery (rising 7th graders) work together to solve.

Try out this (slight variation) on a question BEAM students solved last summer. (Answer below the problem.)

PROBLEM:

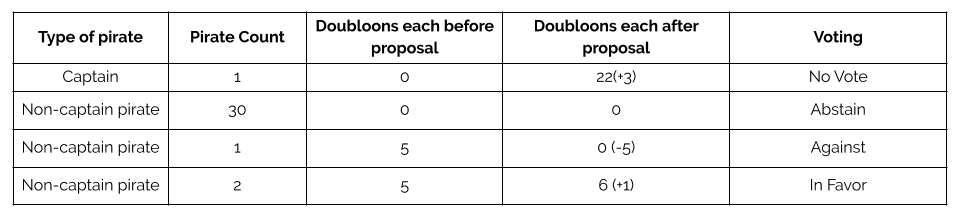

A pirate ship with a crew of 34 half-rate pirates captured a measly booty of 34 doubloons (pirate money). To avoid a mutiny the captain divided the money evenly, giving everyone (including herself) exactly one doubloon to start off.

The captain can make a proposal to redistribute doubloons, but more pirates must vote in favor than vote against for it to take effect, and the captain does not even get a vote! (Other crew members can choose not to vote at all, which is called abstaining.)

If the captain proposes a new way to distribute the 34 doubloons, then the crew takes a vote. Pirates will always vote in favor if it means they get more doubloons after the vote. Pirates will always vote against if it means they lose some of their doubloons. Pirates whose share of the booty doesn’t change will abstain. For a vote to pass, it must have more pirates voting in favor than against. The total of all of the booty must always be 34, and all shares must be integers (0 or greater). However, the scheming captain can redistribute the booty many times: she might make one proposal, then another, then another, changing each pirate's share multiple times.

What is the most doubloons the captain can acquire?

Scroll down for the answer.

Solution:

Let’s first consider a few scenarios to understand how the voting and passing of proposals work.

Example of a proposal that wouldn’t pass: Suppose the captain proposes that 2 pirates plus herself receive doubloons from 3 other pirates, and every other pirate keeps their single doubloon. This would not pass since 3 pirates would vote against (those who lost their doubloon), 2 pirates would vote for (remember the captain doesn’t get a vote!), and every other pirate would abstain. Thus, the proposal fails 3-2.

Example of a proposal that would pass: Now suppose the captain instead proposes that 2 pirates plus herself give doubloons to 3 other pirates, while every other pirate stays the same. Then this proposal would pass 3-2 since 3 pirates receive more doubloons while only 2 non-captain pirates lose doubloons.

Now that we understand how voting works a bit better, a couple questions come to mind:

Can the captain get all 34 doubloons?

Is it even possible for the captain to get two doubloons?

And finally, is there an algorithmic way the captain can get more and more doubloons?

To try to get as many doubloons as possible, the captain might think of proposing that she and 16 other pirates receive a doubloon from each of the other 17 pirates:

But this proposal would fail 17-16. After some thought, it doesn’t seem like the captain can get any doubloons no matter how arrr-dously she try, which leads to step 1.

STEP 1:

The captain arrr-rives at the conclusion that she must give away her doubloon and arrr-gues to her shipmates that it’s best for everyone for half of them (including herself) to give their doubloon to another pirate.

STEP 2:

Now this captain realizes that a pirate will vote in favor whenever they gain doubloons no matter how many, and will vote against no matter how many they lose. So she can take all the doubloons away from pirates with many and just give one each to just enough to outvote them. She proposes that of the 17 pirates with doubloons, a little under half will get just one more doubloon, while a little under half will lose all their doubloons! Of course, she will receive all the extras. The 16 landlubbers without doubloons will still have nothing.

Scheming, the captain realizes that with each proposal she can take almost half of the remaining booty for herself, using half + 1 of the crews’ doubloons to pay off the crew who still have doubloons to lose. So, she goes on in this fashion for 3 more votes (see Steps 3-5), until she, the first mate, and the second mate are the only ones with any doubloons (see Step 6).

STEP 3:

STEP 4:

STEP 5:

STEP 6:

Up until now, the captain had kept the first mate and second mate happy by promising them more and more doubloons with every vote, but with one final proposal she turns the table on them, taking the dozen doubloons they have between the two of them and giving 3 of them away to secure the vote. She makes off with a tidy 31 doubloons and 3 loyal (short-sighted) crew members. The remaining 30 pirates are left scratching their heads over how they gave away all their loot.

Some questions to ponder

Can you do even better than this scalawag of a captain? Would her strategy have worked if they had captured 66 gold coins instead, or 130 treasure chests? Is there anything special about the number 34 (or 66 or 130)?

Announcing BEAM NYC High School Results!

In New York City, every 8th grader in the public school system must apply to go to high school.

The application process is incredibly important because the high school a student attends is one of the biggest predictors of their future opportunities. Yet it is also incredibly difficult for many students, particularly those from disadvantaged communities and under-resourced middle schools, who must often figure things out largely on their own.

BEAM is there to help them bridge that gap.

BEAM helps eighth graders navigate the whole process, from personalized guidance on finding strong-fit schools, to information sessions and interview preparation.

Now the exciting part: BEAM 8th graders have received their admissions results!

Overall, 51% of BEAM students earned spots at high schools that BEAM rates as Tier 1. An additional 18% were offered seats at Tier 2 schools, and 21% earned spots at Trusted schools. In total, 90% of BEAM students earned spots at schools that BEAM rates as Trusted or higher.*

These results demonstrate achievement far outside of typical outcomes for underserved students in New York City.

*BEAM rates NYC high schools as Tier 1 (offers calculus and greater than 85% of students who begin in 9th grade graduate prepared for college), Tier 2 (good course offerings and greater than 70% of graduates are prepared for college courses), or Trusted (good support and acceptable course offerings). Of 400 public high schools in NYC, only about 40 qualify as Tier 1 by these metrics. All Tier 1 schools are highly selective for admissions, and many Tier 2 schools are, as well. Tier 1 schools include specialized high schools, like Brooklyn Technical High School, and early college programs, like Bard High School Early College.

Here’s a complete list of high schools admissions for BEAM students to date:**

Bard High School Early College (10)

The Beacon School (4)

Manhattan Center for Science and Mathematics (9)

Manhattan/Hunter Science High School (2)

University Heights High School (5)

Benjamin Banneker Academy

Midwood High School (4)

Young Women's Leadership School

Central Park East High School (2)

East Side Community School

Academy of American Studies

Aviation Career & Technical Education High School (4)

Bedford Academy

Frank Sinatra School of the Arts High School

Leon M. Goldstein High School for the Sciences

Maspeth High School

Medgar Evers College Preparatory School (2)

Park East High School

A. Philip Randolph Campus High School

Academy for Software Engineering

High School of Telecommunication Arts and Technology

Pace High School

Pathways in Technology Early College High School

Urban Assembly Gateway School for Technology

Urban Assembly Maker Academy (2)

Urban Assembly NY Harbor School

Urban Assembly School for Applied Math and Science (2)

Urban Assembly School for Criminal Justice

Wadleigh Secondary School for the Performing & Visual Arts

Washington Heights Expeditionary Learning School (2)

Inwood Early College for Health and Information Technology

Mott Hall Bronx High School

Repertory Company High School for Theatre Arts

The Williamsburg High School of Art and Technology

BEAM students also received admissions offers from the following Specialized High Schools:

Brooklyn Latin (4)

Brooklyn Technical High School (2)

High School for Math, Science and Engineering at City College (2)

Queens High School for the Sciences at York College

Stuyvesant

Students admitted to Specialized High Schools will choose between these schools and other admissions offers they received.

We are incredibly proud of our students!

Abay was admitted to Bard High School Early College (BHSEC) Queens.

Sarah was admitted to Manhattan Center For Science and Mathematics.

Zhixing was admitted to Brooklyn Technical High School.

Nathaniel was admitted to Park East High School.

Emma was admitted to The Brooklyn Latin School.

Jason was admitted to Aviation Career & Technical Education High School.

Adrianna (Adri) was admitted to Bedford Academy High School.

**We say to date because every year a few BEAM students are under-matched in this process. We are currently working with students who were not admitted to high schools that meet our standards to make sure that they can navigate the appeals process and find a good fit for the next four years.

Got a few minutes and want to learn more about NYC high school admissions? Read this New York Times article about how game theory helped improve New York City’s high school application process.